“The MAGA Ideology and the Trump Regime,” Monthly Review 77, no. 11 (May 2025), pp. 1-24.

The overall rationale behind these moves was provided by another Heritage Foundation document, also published in 2022, titled How Cultural Marxism Threatens the United States—And How Americans Can Fight It by Mike Gonzalez and Katharine C. Gorka, who went on to write NextGen Marxism: What It Is and How to Combat It (2024).10 Cultural Marxism, which is seen on the MAGA right as pervading the universities and government, as well as penetrating into corporations, is viewed as having its genesis in Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, which broke with the economism of classical Marxism. In this distorted view, the new “Cultural Marxism” was carried forward by Frankfurt School Marxists like Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Erich Fromm. It was to be given a more expansive form by postmodernists like Michel Foucault, ultimately leading to radical feminist theory and CRT. The work of Gonzalez and Gorka does not demonstrate the slightest attention to genuine scholarly research. Its purpose is not to promote intellectual inquiry, but rather a New McCarthyism. In their book, they claim that Joseph McCarthy in the anti-Communist witch hunt of the 1950s had carried out “important work,” but made the mistake of leveling charges that he “could not substantiate.” In today’s Cold Civil War, it is suggested, the McCarthyism needs to be resurrected on more solid foundations so as not to make the mistakes of the past—though in fact, the New McCarthyism is as devoid of substance as its 1950s predecessor.11

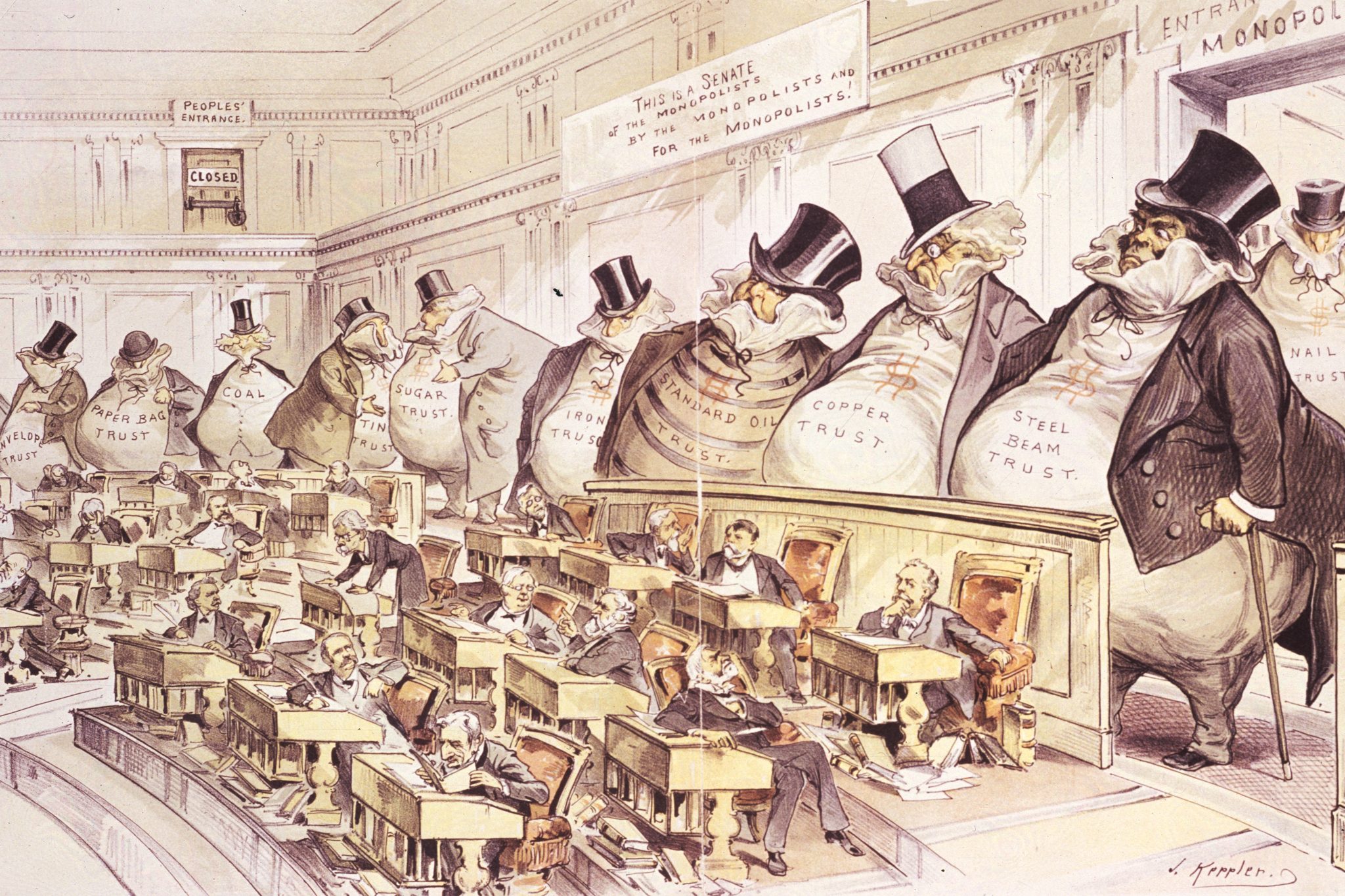

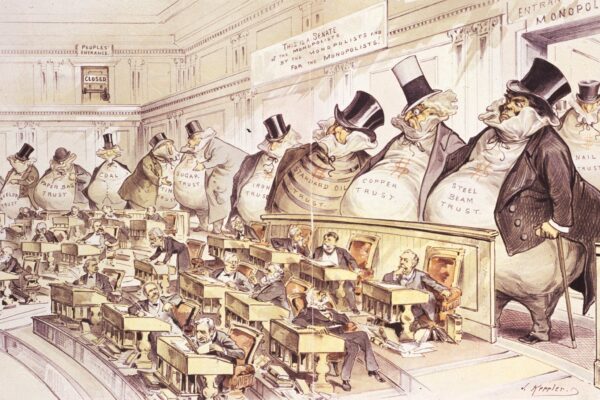

The MAGA ideology that is now ensconced in the White House, and which has also spread to a considerable extent into the courts and Congress, has little to do with Trump himself, for whom it has served as a convenient weapon in his rise to power. Rather, its material basis is to be found in the growth of a larger neofascist movement, which, like all movements within the fascist genus, is rooted in a tenuous alliance between sections of the monopoly-capitalist ruling class at the top of society and a mobilized army of lower-middle class adherents far below. The latter see as their chief enemies, not the upper echelons of the capitalist class, but the upper-middle class professionals immediately above them and the working class below.12The primarily white lower-middle class overlaps with rural populations and adherents of religious fundamentalism or evangelicalism, forming a right-wing, revanchist historic bloc.

The current mobilization of the lower-middle class by the right wing of monopoly capital, particularly, the tech, finance, and oil interests, is initially aimed at dismantling the present “administrative state,” replacing it with one more conducive to a neofascist project. Nevertheless, in the process, a widening political gap is already opening up between the billionaire rulers above and their MAGA army below, between different elements within the evangelical movement, and among those supporting a political dictatorship and those wishing to retain liberal-democratic constitutional forms.13

In line with all movements in the fascist genus, the current regime will inevitably betray its mass MAGA supporters on the radical right, seeking to relegate them to a more and more subservient and regimented role and negating any policies in fundamental conflict with its capitalist-imperial ends. Nevertheless, a mass of think tanks and influencers has arisen that seek to rationalize the irrational, building on those ideological elements that appeal to a white lower-middle class, but ultimately serving the needs of the billionaire capitalist class. Understanding the basis of this new irrationalism and the forms of class rule associated with it is crucial in the counter-hegemonic struggle for a democratic, egalitarian, and sustainable—and thus socialist—future for humanity as a whole.

MAGA’s Neofascist Ideology

“The antonym of fascism,” Marxist economist Paul M. Sweezy wrote in 1952, “is bourgeois democracy, not feudalism or socialism. Fascism is one of the political forms that capitalism may assume in the monopoly-imperialist phase.”14 In the classical definition originating with Marxist theorists—and employed, as in the case of Franz Neumann’s Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism, in the Nuremberg trials—those movements and regimes belonging to the fascist genus have their material foundations in a tenuous alliance between monopoly capital and a mobilized petty bourgeoisie or lower-middle class. The latter were referred to by C. Wright Mills as the “rearguarders” of the capitalist system due to their generally regressive ideology, a product of their contradictory class location.15

Such mobilization of the lower-middle class/stratum at the instigation of sections of monopoly capital occurs when the upper echelons of society see themselves as threatened by a variety of internal and external factors that jeopardize their hegemony. This leads to attacks on the liberal democratic state and the seizure of state power by a section of the ruling class, backed by an army of adherents from below—often initially by legal means, but soon crossing constitutional boundaries. Power is concentrated in the hands of a leader, a duce or Führer, behind whom lies giant capitalist interests. Key to fascist rule, once it gains its ascendancy over the state, is the privatization of large parts of government on behalf of monopolistic capital, a concept first articulated in relation to Adolf Hitler’s Germany.16 This is accompanied by extreme repression of segments of the underlying population, often as scapegoats. Such movements inevitably seek to secure their rule ideologically by gaining control of the entire cultural apparatus of society in a process that the Nazis called Gleichschalthung, or bringing into line.

This general understanding of fascism was dominant in the 1930s and ’40s, extending into the late twentieth century. However, fascism, as a political formation, was eventually reinterpreted in liberal discourse in idealist terms as a pure ideology, conceptually decoupled from its class and materialist foundations and reduced to its outward form as extreme racism, nationalism, revanchism, and the growth of authoritarian personalities, all of which were seen as disconnected from capitalism itself. Much of this was in fact implicit in the criticism of “totalitarianism” developed by Cold War figures like Hannah Arendt, which presented fascism as an extreme system on the right conceptually divorced from capitalism, and the antonym of communism on the left.17 Fascism thus was reinterpreted in the hegemonic ideology as a form of violent authoritarianism/totalitarianism and a departure from capitalism, which was then identified exclusively with liberal democracy. Lacking any real historical-material foundations and ignoring class realities, such reformulations were mere means of shoring up the notion of capitalism itself and have proven useless in attempts to understand the reemergence of fascist and neofascist forces in our time.

In addressing the current neofascism, it is crucial to see it as a product of material/class/imperial relations of late capitalism, which is not to be understood simply in terms of its “populist,” hyper-racist, hyper-misogynist, or hyper-nationalist outer forms but rather in terms of a substantive class-based critique.18 Fascism is at all times an attack on liberal democracy and the substitution of an iron-heel political order under the reign of monopoly-finance capital. Its revanchist ideology does not arise primarily from monopoly capital itself, but rather is chiefly a mechanism for the mobilization of right-wing forces drawn predominantly from the lower-middle class, enlisting an army of actual or would-be stormtroopers (whether wearing black shirts, brown shirts, or MAGA hats), and providing the justification for the dismantling of the liberal-democratic state.

Although it is the real material-class forces rather than disembodied ideology that have to be kept primarily in mind, it is nonetheless true that ideas, once they emerge, can themselves become material forces. “Ideology,” Georg Lukács wrote, is “the highest form of [class] consciousness.”19 If we want to understand the nature of the emerging MAGA regime, we therefore have to explore its governing ideology and its forms of political organization. Very little of this, it should be underscored, emanates from Trump himself, who is often described within the MAGA movement as a somewhat defective, if useful, instrument of the new order.20

Despite its importance in publishing Project 2025, the leading think tank for the Trump movement is not the Heritage Foundation, but rather the Claremont Institute, founded in 1979 in Upland, California. The Claremont Institute was originally a base for Straussian thought (derived from the ultraconservative political theorist Leo Strauss) but has evolved into the nerve center of MAGA. Its funding comes from megadonors, including the Thomas D. Klingenstein Fund (a multibillion dollar fund managed by investment banker Thomas D. Klingenstein, chairman of the board of the Claremont Institute), the Dick and Betsy DeVos Foundation (managed by billionaire former Trump education secretary Betsy DeVos), the ultraconservative Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, and the Sarah Scaife Foundation.21 Its two main publications are The American Mind and the Claremont Review of Books. The Institute also has an additional branch, the Claremont Institute Center for the American Way of Life, located in Washington, DC, across from the Capitol. Academics and pundits associated with the Claremont Institute dominate Hillsdale College in Michigan. Hillsdale publishes Imprimis, essentially a Claremont Institute MAGA publication. The Institute offers a number of fellowships, including the Lincoln Fellowship. Its website tracks so-called “BLM funding” (referring to the Black Lives Matter, or BLM movement) by corporations, claiming, on extremely questionable grounds, that $82.9 billion has been directed to the CRT/Woke/Cultural Marxist cause by corporations. As in MAGA ideology in general, corporations are condemned as morally corrupt for giving way to Cultural Marxism but are seldom criticized economically. This is consistent with the entire history of petty-bourgeois ideology as reflected in the nineteenth-century writings of such celebrated figures as Thomas Carlyle and Friedrich Nietzsche, whose ideological outpourings, as Lukács noted, reflected “a contradictory twofold tendency” of a “critique of capitalist lack of culture,” while nonetheless supporting an order “located in capitalism.”22

In 2019, Trump awarded the Claremont Institute the National Humanities Medal. On January 6, 2021, lawyer John Eastman, a member of the board of the Claremont Institute (where he remains to this day), supported by other Claremont Institute associates, played the leading role in organizing the MAGA assault on the Capitol Building in Washington, DC. He also wrote the key memos directed at pressuring Vice President Mike Pence to invalidate the 2020 election in an attempt to reverse Trump’s loss to Joe Biden. All of this earned Claremont the reputation as the January 6 attempted coup’s “brain trust.”23

The Claremont Institute was to become the main intellectual incubus of Trump II. More than a dozen Claremont associated pundits and former Claremont fellows regularly appear on Fox News. This includes, in addition to Eastman, such luminaries as Michael Anton, Claremont senior fellow and a high-level Trump State Department appointee; Christopher Caldwell, contributing editor to the Claremont Review of Books and white supremacist commentator; Brian T. Kennedy, Claremont former president and current board member, and chairman of the Committee on the Present Danger, which advances a new McCarthyism; Charles R. Kesler, Claremont Review of Books editor and leading proponent of a “Cold Civil War”; Charlie Kirk, former Claremont Lincoln Fellow and founder/CEO of Turning Point USA (TPUSA), with its “Professor Watch List” and its evangelical branch, TPUSA Faith; John Marini, Claremont senior fellow and leading right-wing intellectual critic of the “administrative state”; and Christopher F. Rufo, former Claremont Lincoln Fellow and notorious anti-CRT pundit.

Anton, a former managing director of investment at BlackRock and currently a senior researcher at the Claremont Institute, served as deputy assistant to the president and deputy national security advisor for strategic communication on the National Security Council in Trump’s first administration.24 He is now director of policy planning in the U.S. State Department under Marco Rubio. It was Anton more than any other single figure who connected the Claremont Institute to MAGA and the alt-right. His 2016 Claremont Review of Books article “The Flight 93 Election”—using the metaphor of the passengers who rushed the cockpit on the terrorist flight on September 11, 2001—was to go viral and played a major role in mobilizing militant support for the Trump campaign. Here Anton declared that the 2016 election was a “charge the cockpit or die election,” in which “you may die anyway” in the attempt, but if Hillary Clinton were to be elected, “death is certain.” Although the piece was disjointed, rambling, and illogical, the metaphor nonetheless caught on, catapulting Anton to right-wing celebrity status, and led to his appointment to Trump’s National Security Council with the support of the right-wing tech billionaire Peter Thiel.25

In 2019, Anton published After the Flight 93 Election… And What We Still Have to Lose, which emphasized the need for a war on the entire left, earning the praise of Trump. This was followed in 2020 by his book, The Stakes: America at the Point of No Return, in which he proposed that immigration should ideally be stopped altogether, while birthright citizenship (citizenship by virtue of simply being born in the United States, even if not to U.S. citizens) should cease immediately. China was the primary enemy, while peace should be made with Russia. The latter, Anton explained, belonged to the same “civilizational ‘sect’” as the United States and Europe, “in ways that China would never be.” Anton’s The Stakes, however, is best known for his explicit advocacy of a “red [that is, Republican or right-wing] Caesarism,” in which the presidency would become a “form of absolute monarchy” or “one-man rule” exhibiting widespread popular support—a position that was followed immediately after in his book with the exhortation to “reelect Trump!” Only when elected would Trump declare himself Caesar.26

In a review on “Draining the Swamp” in the Claremont Review of Books, Anton popularized Marini’s Unmasking the Administrative State. Marini’s analysis is seen as a validation of Alexandre Kojève’s conservative rendition of G. W. F. Hegel’s German idealist philosophy, which in the right-wing view is seen as forming a justification for autocratic bourgeois rule as the end of history. Applied to contemporary institutions, the bureaucratic overlords of the administrative state are to be viewed as the “ruling class.” Marini and Anton thus argue that there is a need for Trump to smash the administrative state and replace it with more centralized rule. These same views led U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who in an earlier stage of his career had employed Marini as a special assistant, to exclaim “We must read Marini!!”27

Anton has declared that in order to win “we need bloggers, meme-makers, Twitter trolls, street artists, comedians, propagandists, theologians, playwrights, essayists, novelists, hacks, flacks, and intellectuals”—as well as Trump and right-thinking capitalists.28 His most iconoclastic act within the Claremont Institute itself was to write an article about the alt-right Nietzschean-fascist propagandist Bronze Age Pervert (known as BAP, now revealed as Romanian-American Costin Vlad Alamariu, who received a PhD from Yale), the author of Bronze Age Mindset. Anton’s role, in a 2019 Claremont Review of Books article titled “Are the Kids Al(t) Right?,” was to bring BAP/Alamariu into the MAGA mainstream in an effort to draw disenchanted white youth into the neofascist movement. Noting that BAP provided in his self-published Bronze Age Mindset a “simplified pastiche of Friedrich Nietzsche,” which had “cracked the top 150 on Amazon—not, mind you, in some category within Amazon but on the site as a whole,” Anton argued that it represented an opportunity for the MAGA right to dominate the underground youth discourse. BAP characterized the liberal elites, intellectuals, left thinkers, and the general population as “bugmen,” without heroism, similar to Nietzsche’s “Last Man.” Human beings in general were portrayed as belonging to mere “yeast” life. The solution lay in male bodybuilding through weightlifting, and the cultivation of the image of Greek Bronze Age heroes. BAP is a white supremacist, emphasizing Aryan purity and vile attacks on diverse populations everywhere. As Anton himself admitted, “the strongest and easiest objections to make to Bronze Age Mindset is that it is ‘racist,’ ‘anti-Semitic,’ ‘anti-democratic,’ ‘misogynistic,’ and ‘homophobic,’” making it more “outrageous” than Nietzsche. Yet, he pretends that BAP is “gentler” than thinkers like Karl “Marx, [V. I.] Lenin, Mao [Zedong]…[Che] Guevara, [Saul] Alinsky and Foucault, or any number of fanatics whose screeds are taught in the elite universities.” In the end, Anton underscored the importance of BAP’s attacks on “bugmen” and “bugtimes,” incorporating his views within MAGA.29

A study of Bronze Age Mindset itself reveals venomous references to “the shantytowns of the Turd World,” and attacks, citing Nietzsche, on “pre-Aryan modes of life, the return of socialism, of the longhouse, feminism,” and “Satanic Marxist sects.” Athenian general Alcibiades, conquistadors Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, Napoleon Bonaparte, Theodore Roosevelt, Alfredo Stroessner (former dictator of Paraguay), and especially Bob Denard (a brutal twentieth-century French mercenary active in the Congo and the Comoros Islands) are BAP’s models of the return in modern times of Bronze Age Aryan humans. BAP’s favorite president, prior to Trump, is James K. Polk, who launched the Mexican-American War. The “white population” in the United States, he writes, seized Mexico “by their valor.” Feminism is seen as an abomination. “Nothing so ridiculous as the liberation of women,” BAP/Alamariu declares, “has ever been attempted in the history of mankind,” which he describes as an attempt to “return to pre-Aryan matriarchy.” He adds, “Social justice is a disgusting parasitism.” Today’s cities, subject to waves of immigrants, are “populated by hordes of dwarf-like zombies that are imported for slave labor and political agitation from the fly-swept latrines of the world.” He openly claims: “I believe in Fascism or something worse.” For all these reasons, according to BAP, Trump is to be supported in his conquest of government. “The Leviathan” of the administrative state dominated by the “bugmen,” he insists, must be smashed in order to create a new “primal order.” With the support of Anton and others, BAP was recognized as a kind of underworld Nietzschean influencer behind the MAGA movement, attractive to young, regressive white males. He was to become virtually required reading for young white staffers in the first Trump administration.30

Anton was himself encouraged to read BAP by self-styled “Dark Enlightenment” thinker Curtis Yarvin, a neofascist close to both Anton and Vance (the MAGA heir apparent). Like Vance and Anton, Yarvin is heavily supported by Silicon Valley billionaire Thiel. Yarvin is also openly admired by Trump adviser and Silicon Valley venture capitalist Marc Andreessen for his antidemocratic views. Vance calls Yarvin, whom he has also referred to in friendly banter as a “fascist,” “my number one political influence.” In the MAGA world, Yarvin remains something of a shadowy figure, despite the fact that he has articulated the more reactionary strategies of the Trump regime. He is an ex-computer programmer and right-wing blogger, writing under the pseudonym Mencius Moldbug and advocate of a “Dark Enlightenment” or neoreactionary movement (“NRx”). Tucker Carlson devoted an entire show to interviewing Yarvin in 2021. He is best known for his anti-democracy arguments and insistence that the president can establish himself as a “national CEO” or even “dictator,” concentrating all power in the executive branch and superseding the legal system and the courts while shifting from an “oligarchical Congress” to a “monarchical president.” Americans, he insists, are “going to have to get over their dictator-phobia.”31

Yarvin has weaponized J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, seeing the leftist elite or professional-managerial class as an “elf aristocracy,” the “lower-middle class” as “hobbits,” and “dark elves” like himself as defenders of the hobbits. Like Steve Bannon, Trump’s former White House chief of staff, with whom he identifies, Yarvin sees himself as a proponent of MAGA; but, unlike Bannon, he deemphasizes the contradiction between the lower-middle class MAGA forces and the monopoly-capitalist billionaires at the top. Yarvin’s real allegiances are to the billionaires, rather than the lower-middle class. Indeed, he denies that he is a real fascist, despite the fact that he has applied the fascist label to himself, characterizing himself rather as a more straightforward supporter of dictatorship (or monarchy), since he has absolute contempt for the masses. Nevertheless, Yarvin sardonically states, “frankly, Hitler reads a lot like me”—if, he acknowledges, more talented and more evil.32

Widely seen as a largely underground figure who has helped game the system for Trump, Yarvin has provided the general plan for an imperial presidency. He argues that real power is held “oligarchically” (distinguished from the classical notion of oligarchy as based on wealth) by people who control the media and the universities, constituting the “Cathedral.” The Cathedral can only be toppled by a monarch or dictator, acting as a CEO. Once Trump was elected, Yarvin contended, he could purge the federal bureaucracy (what Yarvin calls “RAGE,” or retire all government employees) by claiming he had an electoral mandate allowing him to transgress the law and bring both the courts and Congress to heel. All court orders requiring the president to desist should be ignored. The mainstream media corporations and the universities should be closed down. In a podcast, Anton said to Yarvin, “You’re essentially advocating for someone to—age-old move—gain power lawfully through an election, and then exercise it unlawfully.” Yarvin responded, “It wouldn’t be unlawful. You’d simply declare a state of emergency in your inaugural address.” The president could apply this to every state and take “over all law enforcement authorities.” Like Anton, Yarvin declared of the president, “you’re going to be Caesar.”33

Anton has stated that the universities are “evil,” a position strongly supported by Rufo, a former director at the intelligent design (creationist) Discovery Institute and a Claremont Lincoln Fellow.34 Rufo is widely celebrated in MAGA circles for his grand propagandistic exploits in turning CRT and DEI into toxic conceptions in the public mind. He is currently a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research and a contributing editor to its City Journal. In “Critical Race Theory: What It Is and How to Fight It” for Hillsdale’s Imprimis, Rufo argued that CRT was the product of Cultural Marxism and “identity-based Marxism.” In what has become a fundamental element of MAGA ideology, he contends that today’s Marxists are all identity-theorists and are opposed to “equality,” replacing it with “equity,” which is “little more than reformulated Marxism.” CRT, he pronounces, promotes “neo-segregation.” It violates the principle of civil rights and is discriminatory through its anti-white policies. In this way, civil rights law is to be redirected against racial minorities. Rufo associates CRT and BLM with anticapitalism and reverse racism. His assaults on CRT influenced Trump’s attacks on it in his first administration.35

More recently, Rufo has argued for “laying siege to the institutions.” This includes attacking any corporations that instituted DEI policies, seen as the product of Cultural Marxism, CRT, and BLM—a neo-McCarthyite view shared by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. Major targets are “radical gender theory” and what Rufo calls “the transgender empire.” He contends that “we must fight to put the transgender empire out of business forever.” Rufo and the MAGA right fulminate against the “college cartel” and argue that K–12 reeducation should start with the promotion of “Western Civilization.”36

One of the most adamant critics of diversity on the MAGA right is Caldwell, who in his article “The Browning of America” argues that “‘Diversity’ has [always] been an attribute of subject populations.” Hence, recognizing it as a basis of social policy flies in the face of the principles of the founders of the U.S. Constitution. In an article on Robert E. Lee, Caldwell argued that left criticisms of the commander of the Confederate forces as a defender of the slaveholding South, and thus of slavery, were aimed at eliminating Lee as “the moral force of half the nation.”37

Claremont Review of Books editor Kesler, a member of Trump’s 1776 Commission on U.S. History, intended to counter the 1619 Project on the history of U.S. slavery, has been a leading figure in promoting the MAGA notion of a Cold Civil War between the right and the so-called dominant forces on the left. The term “woke,” which arose first in the civil rights movement, has been massively turned around by the right since 2019, relying on conservative command of the media, to refer in a derogatory way to all contemporary progressive political and cultural causes. It is employed as a means of belittling social justice struggles against racism and gender inequality, while its most common usage is as a racist dog whistle.38

The MAGA ideology’s Cold Civil War is closely attached to attacks on China. As chairman of the Committee on the Present Danger (which includes Bannon as a member), Claremont Institute board member Brian Kennedy is part of a movement to generate a new McCarthyism focused on Beijing. Claiming that Chinese Communism has infiltrated U.S. society in BLM clothing, he writes: “We are at risk of losing a war today because too few of us know that we are engaged with an enemy, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) [sic], that means to destroy us.”39

Christian nationalists are also being enlisted in the Cold Civil War/New McCarthyism. Kirk’s Turning Point USA became notorious in 2016 for its Professor Watch List, singling out mostly left academics across the country to be targeted by the right in a McCarthyite manner. Kirk, who also served on Trump’s 1776 Commission, has now become known as a mega “whisperer” to youth, in which he bullet points the “war on white people” and encourages white nationalism. His organization, working with the Claremont Institute, bussed MAGA supporters to the January 6, 2021, protest and assault on the Capitol. Yarvin, who has described slavery “as a natural human relationship” and promoted biological determinism and monarchy, was effusively praised by Kirk on his radio show and podcast, along with white supremacist Steve Sailer. Kirk is the author of Right Wing Revolution: How to Beat the Woke and Save the West, published in 2024. According to the publisher’s blurb, “America…is under threat from a lethal ideology that seeks to humiliate and erase anyone that does not bow at its altar…. Kirk drags wokeism out of the shadows and details the exact steps needed to stop its toxic spread,” which “has already seeped into every aspect of American society.”40

More recently, Kirk has transformed himself into the leading promoter of evangelical Christian nationalism within the MAGA movement, establishing a division of Turning Point USA called TPUSA Faith aimed at white evangelicals. He argues that the U.S. founders created a Christian nation and advocates the Seven Mountain mandate of extreme evangelical Christian nationalism, in which believers are required to seek to dominate all of reality, including family, religion, education, media, arts, business, and government. This is tied to endism and religious apocalypticism (Second Coming) views. Kirk has sought to promote hatred of LGBTQ+ and transgender people in order to motivate the evangelical movement to take on a more direct political role.41

OMB director Vought is undoubtedly the most powerful Christian nationalist within the Trump administration itself. Writing in 2022 for the Claremont Institute’s The American Mind, Vought claimed that the Center for Renewing America, which he founded in 2021, had demonstrated on so-called legal grounds that “illegal aliens coming across” the U.S.-Mexico border constituted “an invasion,” thus allowing state governors, who, according to Article 1, Section 10, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, are not allowed to “engage in War unless actually invaded,” to act forcibly against these “invaders,” independent of the federal government.42 As a Christian Nationalist organization, the Center for Renewing America is adamantly anti-Palestinian, opposing any attempt to allow Palestinians to immigrate to the United States, arguing that “One would be hard-pressed to identify a people or culture more fundamentally at odds with the foundations of American self-government than Palestinians,” who have “a culture poisonous to the health of and integrity of American communities,” and whose ideology, despite the counter-claims of “intersectional Marxists,” has as its aim the total annihilation of Israel. Vought’s Center for Renewing America is strongly in favor of the removal of the Palestinian population from Gaza and their resettlement in the lands of the Arab League.43

Movements in the fascist genus have often relied on opportunistic shifts from left to right. A classic example of this is the Italian leftist thinker Enrico Ferri, a reactionary pseudo-socialist who was strongly attacked by Frederick Engels, and later became a follower of Benito Mussolini.44 The main intellectual vehicle for so-called “leftist” cooperation with MAGA ideology, operating in what is presented as a common anti-liberal vein, is Compact magazine, cofounded by Iranian-American rightist and former Trotskyist Sohrab Ahmari, a close associate of Vance and now the U.S. editor of UnHerd, and by national-populist Edwin Aponte, editor of Bellows, a MAGA-style publication. Compact magazine was once described in Jacobin as a “syncretic” magazine of both left and right.45 However, rather than representing some sort of meeting point of left and right, it is strongly supportive of Trump and Vance while successfully drawing in erstwhile leftist contributors, such as Christian Parenti and Slavoj Žižek (a contributing editor) into a publication in which pro-MAGA views are hegemonic.46 Yarvin, Anton, Caldwell, and Rufo have all written multiple articles for Compact on such topics as the nihilism of the left-wing ruling class, Cultural Marxism, CRT, dismantling the administrative state, and support for Viktor Orbán’s ultra-conservative government in Hungary and the neofascist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany.47

Parenti, once a well-known leftist journalist, writes regularly for Compact. His columns have supported Trump’s nomination of Kash Patel as FBI director and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as Secretary of Health. He has also written columns claiming that Trump is an anti-imperialist and that “‘Diversity’ Is a Ruling Class Ideology.” Since Trump’s reelection, Parenti has presented Trump and some of his department heads (Kennedy, Patel, and Tulsi Gabbard, Trump’s Director of National Intelligence) as potential opponents of the “deep state” or surveillance-intelligence state, and thus in line with the left in this respect. However, this is a gross misperception of the nature of the Trump/MAGA regime itself, which has nothing to do with openness or democratic control, but which is establishing the basis for its own direct rule.48

Žižek has used Compact as a venue in which to engage in the most reactionary themes. Thus, in an article titled “Wokeness Is Here to Stay,” he presented a transphobic argument in which he declared that “the use of puberty blockers is yet another case of woke capitalism.” In this same anti-woke article, Žižek generalized from the experience of a Black professor who was strongly criticized by students from an Afro-pessimist standpoint (as detailed in a different Compact article). From there, Žižek went on to make the extraordinary racially charged statement, directed at a mainly white reactionary readership, that, “The black woke elite is fully aware that it won’t achieve its declared goal of diminishing black oppression—and it doesn’t even want that. What they really want is what they are achieving: a position of moral authority from which to terrorize all others.”49

Compact magazine managing editor Geoff Shullenberger has specialized in bringing the ideas of BAP into the MAGA mainstream, both within Compact and elsewhere. Shullenberger also is the coeditor of COVID-19 and the Left: The Tyranny of Fear, opposing lockdowns, vaccine mandates, and masking in response to COVID-19 as due to the extremism of the left. Meanwhile, Compact columnist and MAGA “populist” supporter Batya Ungar-Sargon, author of Bad News: How Woke Media is Undermining Democracy (2021), was appointed in 2025 deputy opinion editor of Newsweek.50

The MAGA think tanks are a product of funding by big capital interests, often promoting, in this respect, a libertarian ideology, but melding this with the need to reach the white lower-middle class with its reactionary, nationalist-populist, revanchist, racist, misogynist, and anti-socialist perspective, as a way of developing a mass constituency. The resulting MAGA ideology is disseminated through wider media such as Fox News, talk radio, social media, YouTube videos, blogs, and podcasts. The influential infotainment site Breitbart, once headed by Bannon, has published numerous articles attacking Cultural Marxism, and specializes in sensationalized shock attacks on the left. Breitbart’s senior technology editor, Allum Bokhari, a former Claremont Lincoln Fellow, has written for Hillsdale’s Imprimis on the need for the right to control big tech, along the lines subsequently implemented by Musk at X.51

Claremont Lincoln Fellow Raheem J. Kassam, a former chief of staff to Brexit leader Nigel Farage and a Bannon ally, is the former editor-in-chief of Breitbart London. More recently Kassam had cohosted Bannon’s MAGA radio show/podcast “War Room.” In 2018, Kassam became editor-in-chief of the Trumpist news website National Pulse, and appears frequently as an “expert” commentator on Fox News, where he has discussed “How Did America Fall to Marxism?”52

MAGA analyses are also disseminated by way of conservative book publishing. Rufo’s best-selling America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything (2023) and Kirk’s The MAGA Doctrine (2020) were both published by Broadside Books, HarperCollins’s imprint for ultra-conservative nonfiction, which absorbed the Fox News book brand. The big five English-language book publishers all have distinct imprints devoted entirely to ultra-conservative books aimed at white supremacist Republicans/MAGA.53 Anton’s After the Flight 93 Election, Kesler’s Crisis of the Two Constitutions: The Rise, Decline, and Recovery of America’s Greatness(2021), Kennedy’s Communist China’s War Inside America (2020), and Ungar-Sargon’s Bad Newswere all published by Encounter Books, established by the right-wing Bradley Foundation, a funder of the Claremont Institute. Established in 1998, Encounter Books deliberately took its name from the pseudo-left-liberal journal Encounter, which was exposed in the 1970s by Ramparts as a CIA-funded publication. Kirk’s Right Wing Revolution: How to Beat the Woke and Save the West (2024) was published with Winning Team Publishing, cofounded in 2021 by Donald Trump Jr.54

All the new right concepts and talking points end up on social media. As Fox News host Jesse Watters stated, “We are waging a 21st-century information warfare campaign against the left. It’s like grassroots guerrilla warfare. Someone says something on social media, Musk retweets it, [Joe] Rogan podcasts it, Fox broadcasts it and by the time it reaches everybody, millions of people have seen it.”55

Division in the Ranks

The most extreme MAGA ideologues such as Bannon, Yarvin, and Anton are distinctly aware that the nationalist-populist MAGA movement is rooted in lower-middle class whites (whom the neofascist movement in both Europe and the United States is accustomed to referring to as “hobbits”), and only secondarily in privileged elements of the working class. MAGA think tanks often present a barely disguised contempt for the “lumpen,” “pitchfork-bearing proletariat,” or “proles,” namely the working class.56 Almost no positive references to the working class or attempts to approach the underprivileged are present in the mainline MAGA literature, which is understood as rooted in a fragile national-populist alliance between the billionaire class and the lower-middle class, both of which see the working class as their most dangerous enemy (exceeding their hatred even for the upper-middle class professional-managerial stratum). Funded by the mega-rich and dedicated to the idea, as Anton says, that “race trumps class,” the MAGA pundits and influencers are unable to address directly the question of the working-class majority without undermining their claim to a broad populism. The result is that they appeal primarily to whiteness and “middle America.”57 Occasional references are made to MAGA hat-wearing truck drivers and other workers, but this only constitutes a vain attempt to elude the reality of a political bloc that consists largely of the lower-middle class and a relatively small number of privileged workers. Although Bannon, representing MAGA’s radical right, refers to workers, it is always in a context where the lower-middle class looms larger.58

This fundamental class division will remain. Although Trump made some gains with blue-collar workers in the 2024 elections, particularly in rural areas, his political base remains the lower-middle class, which is in large part hostile towards the working class below. The Trump program is destined to hit the working class hardest economically.59 It was Anton who was to make the most serious ideological attempt to escape this trap in an article in Compact titled “Why the Great Reset Is Not ‘Socialism,’” in which he sought to examine Marxist theory and turn it on its head. Thus, he characterized Silicon Valley billionaire oligarchs in alt-right fashion as the “left,” the enemy of right-wing populism. Moreover, while the MAGA movement, he recognized, was fundamentally based in the lower-middle/middle class/the poor, its “natural” basis ultimately was to be sought in the majority that he sardonically referred to as the “proles.”60 His whole endeavor in this respect, however, was to fall flat in the face of the inescapable reality of a neofascist alliance between the billionaires and the lower-middle class—both of whom see the diverse working class as the ultimate enemy. Moreover, Anton’s contradictory attempt to create a right-wing populism that incorporated the working class and targeted billionaire oligarchs was at odds with his own role as a member of the national security establishment, dominated by the mega-capitalist class, which had him hobnobbing with some of its biggest players. He therefore quickly mended his ways. Although he persisted in criticizing “oligarchs,” they were refashioned in conformity with the hegemonic MAGA ideology as the members of the administrative state, no longer big money interests.

Yet, if the mass MAGA movement with its racism and its small-property-based outlook is inherently anti-working class, even if it has attracted significant numbers of working-class voters, it also finds itself in conflict with the ultra-wealthy interests that have funded and mobilized it, making it a dangerous movement from the standpoint of monopoly capitalism itself. Once political power is achieved in regimes in the fascist genus, divisions quickly emerge between the top echelons of monopoly capital and its army of lower-middle class adherents. Having obtained control of the state and of the military and police powers, the ultra-wealthy ruling class has every reason to discard the more militant nationalist—often partially anticapitalist—elements of its “radical right” base. The classic historical instance of this was the Night of the Long Knives in Hitler’s Germany, from June 30 to July 2, 1934, in which the Nazi party’s paramilitary brownshirt wing, the Sturmabteilung, or “Assault Division,” known as its stormtroopers, were subjected to a bloody purge. The purge was aimed specifically at the Strasserism (named after Otto and Gregor Strasser), deeply embedded in the brownshirts within the Nazi movement, which was both antisemitic and, to a considerable extent anticapitalist, and belonged to a milieu of militant mass action or “revolutionary” nationalism. Elimination of Strasserism allowed the consolidation of fascism as a reactionary monopoly-capitalist state, repressing and regimenting its mass petty-bourgeois base.61

In the very different conditions of the neofascist MAGA movement in the United States today, these same general contradictions appear, though minus the extreme violence. Many among the MAGA faithful were startled to see their lack of representation in the Trump cabinet following the 2024 election, a sharp contrast from the 2016 election. The Trump regime today has a cabinet of billionaires, surrounded by still further billionaires. Although there are extreme rightist operatives whose views are similar to those of the MAGA masses in the second Trump White House—such as Stephen Miller, who, despite being Jewish, appears to support white Christian nationalism, and is currently deputy chief of staff for policy—they are overshadowed by the mega-capitalists. Right from the start, it was clear that high-tech financial capital rather than the MAGA hat-wearing base was to be in charge. As Gary Stout, a Washington attorney, wrote in Pennsylvania’s Observer-Reporter, Trump “is now creating a new political elite of oligarchs that has no accountability to Congress or loyalty to his own MAGA movement.”62

This contradiction, splitting the MAGA movement/Trump regime, was immediately apparent in the conflict over H-1B visas for foreign workers. These visas are widely used by multinational corporations to hire foreign technical workers in specialty occupations, especially high-tech, bringing in relatively low-paid skilled workers from India, China, and elsewhere. H-1B visas have been heavily criticized within the MAGA movement, since they undercut relatively high-paid U.S. jobs. Voicing the outrage of the MAGA faithful, Bannon declared prior to Trump’s inauguration that Musk, who came out strongly for the H-1B visas, was “evil” and that he would have him driven out of the White House. Bannon raged in national-populist terms against wealthy “oligarchs,” not only “the lords of easy money,” but more importantly the tech overlords of Silicon Valley, representatives of “technological feudalism,” who were now dominating the MAGA movement, and were opposing “the populist, nationalist revolution.” MAGA militant Laura Loomer presented racist arguments in which she declared: “Our country was built by white Europeans…. Not by third world invaders from India.” Openly attacking Musk on X, Loomer suddenly found herself demonetized on the platform.63 The fact that this represented a fundamental division between billionaire monopoly-finance capitalists and high-tech oligarchs at the top and the lower-middle class MAGA base was evident in an article by Kevin Porteus of Hillsdale College titled “Putting Americans First,” published in The American Mind. He advanced the argument that “America First” should mean “Americans…first.”64Breitbart likewise ran story after story against H-1B visas. The rebellion over this issue, however, was soon put down by Trump, who, himself a billionaire, sided with Musk, indicating that his own companies employed foreign workers on H-1B visas. Faced with a division between monopoly-finance capital and his own militant MAGA movement, Trump chose the former.

The fissure between a capitalist ruling class of billionaires and the neofascist movement on the ground will only widen. The MAGA movement expects lower taxes under Trump, which will no doubt be partially forthcoming, but paid for to a significant extent by drastic cuts in social services. Expectations of lower prices, especially with new tariffs being instituted, will be dashed. Moreover, like all tax reductions under monopoly capitalism, the new Trump tax cuts will be highly regressive, benefiting the rich most of all and further widening the gap between the top and the bottom of U.S. society. The cutbacks on civilian government will hurt the vast majority of the population, including the lower-middle class. With nearly all social spending that benefits the bottom 60 percent of the population, including Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security now in the crosshairs of Musk’s DOGE, the carnage is likely to be severe. Although the MAGA movement is characterized by extreme nationalism, monopoly-finance capital and its high-tech overlords are geared to accumulation on a world scale and global financial expropriation. They rely on the exploitation not only of the global proletariat, but also the increased exploitation and expropriation of U.S. workers. Implementation of ruling-class policies on globalization, financialization, imperialism, war, and hyperexploitation under the new regime will inevitably push much of the U.S. lower-middle class back into the working class, polarizing and destabilizing the society still further.

Trump’s neofascist regime is a desperate act of a declining empire. It has supplanted neoliberalism only in the sense that the right wing of the ruling class itself is now in direct and open command of the state, seeking to restructure it as a vehicle of resurgent hegemony. The conflict between neofascism as a more regressive global capitalist project designed to preserve and enhance the power of the ruling capitalists with their global interests, on the one hand, and the national-populist movement of the MAGA radical right focused primarily on the conquest of the administrative state, on the other, means that the mega-capitalist interests will continually betray the MAGA “populist” base, viewed as mere cannon fodder in the Cold Civil War.

Trump appointed billionaire Vivek Ramaswamy as the codirector of DOGE along with Musk. Ramaswamy is the founder of the giant pharmaceutical company Roivant Sciences and author of the bestselling 2023 book Woke Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam. He resigned from his DOGE position to run for governor of Ohio. With Ramaswamy departing, Musk was left as the sole power at DOGE. Ramaswamy has played a leading role in attacking corporate ESG and DEI. Recognizing that corporations had increasingly introduced limited ESG and DEI programs in response to environmental and social issues, pundits on the MAGA right, including the opportunistic plutocrat Ramaswamy, were able to make the existence of such programs a popular “anti-corporate” moral issue. The result is that many corporations now have, not unwillingly, reversed themselves in line with Trump. Some have dropped the “diversity” and “equity” from DEI while hypocritically retaining “inclusion.”65

The sheer arrogance of the capitalist oligarchs and their managers can be seen in the rise of Thiel as a dominant figure in the Trump orbit, undoubtedly the most powerful figure connected to the regime with the exception of Musk (and the president himself). In 2022, Thiel characterized himself as leader of a “Rebel Alliance,” as in Star Wars, fighting the “imperial stormtroopers” of the U.S. establishment and engaged in a struggle aimed ultimately at China.66 In 2009, he declared “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible,” causing him openly to reject the latter.67 He is currently tied to six members of the National Security Council who are beholden to him financially and politically and are part of his industrial network: Vance (whose political campaigns were financed by Thiel), Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth (who is associated with Thiel’s military-tech network), Secretary of Energy Chris Wright (who sits on a board of the energy startup Oklo, in which Thiel is a major investor), National Security Advisor Mike Waltz (whose 2022 Florida campaign was funded by Thiel), Rubio (whose 2022 reelection bid was financed by Thiel), and White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles (who is on the payroll of the Thiel-funded Saving Arizona PAC).68

Thiel, like Musk, Ramaswamy, and Trump himself, stands for the interests of the “masters of the universe.”69 Despite libertarian ideology and a neofascist ethos, there is little to connect the financial plutocrats materially with the lower-middle class. Given that the so-called destruction of the administrative state is leading to more centralized monopoly-capitalist control of the state in the interests of the plutocrats, the selling out of the MAGA movement on the ground is palpably obvious.

A further contradiction in the MAGA movement lies in its promotion of its Christian white nationalism, splitting the evangelical movement. Exit polls indicate that some 80 percent of white evangelical voters support Trump. Yet, the freezing of USAID by Trump and Musk generated strong opposition from Christian affiliated aid groups. The resulting deep division in conservative circles undoubtedly affected the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the stoppage on foreign aid. Trump’s establishment of a White House Faith Office headed by the controversial televangelist Paula White-Cain, known for her promotion of the capitalist-oriented “prosperity gospel,” together with his creation of a task force headed by Attorney General Pam Bondi, aimed at ending “anti-Christian bias,” have upset the traditional separation of church and state. This weaponization of evangelicalism to reinforce a Christian nationalism directed at supporting the MAGA state has led to widening criticisms within the evangelical and wider Christian communities.70 Trump’s redoubled support for Israel’s extermination of Palestinians is unpopular with younger evangelicals, who are increasingly rejecting Christian Zionism.

The most potent attack from within evangelicalism has emerged from preachers such as Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, assistant director for partnerships and fellowships in Yale University’s Century of Public Theology and Public Policy, in his 2018 book Reconstructing the Gospel: Finding Freedom from the Slaveholder Religion. Working closely with Protestant minister Reverend William Barber II, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, Wilson-Hartgrove was motivated by his opposition to the Trump movement to address the “original sin” of the dominant white evangelicalism in the United States, which, rather than simply an evangelical movement as such, was from the first a “slaveholder’s religion.” Emerging within the evangelical community itself and receiving considerable acclaim, Wilson-Hartgrove’s critique of the slaveholder’s religion has served to bring into the open the most acute contradictions of the Christian nationalist ideology.71 As he wrote,

The sad reality is that we [evangelicals] chose a side in the 19th century and our movement is still infected by the slaveholder religion that was funded by plantation owners. That faith did not go away after the Civil War; it doubled down and prayed for “redemption” from Reconstruction. And it rejoiced when white supremacy campaigns across the South regained power and established Jim Crow segregation. Mid-20th century, when the balance of power was again challenged by America’s civil rights movement, slaveholder religion reasserted itself, criticizing Dr. King for “politicizing” the gospel and favoring “law and order” systems that perpetuated inequality. The Southern Strategy aimed to harness slaveholder religion by creating a Moral Majority that would feel righteous for their support of the status quo.

Donald Trump did not create the crisis we now face, but his presidency is exposing the truth about who we are as evangelicals—not a movement divided between left and right, but a people of faith who must now choose between slaveholder religion and the Christianity of Christ.72

For “400 years,” slaveholder religion, Wilson-Hartgrove argued, has taught people to fear people of color. “Because slaveholder religion’s god ordained white supremacy, white people learned to fear equality and the black political power that challenged the social order they were taught to value.” It is not a return to the politics of “redemption” that is the answer, he argues, but completing the politics of Reconstruction.73

Betrayal and Revolt

The Trump regime is a regime of betrayal. It is already leading to the abandonment of the lower-middle class, which through the MAGA movement brought it into power, as well as the working-class majority.74 What it offers to its core lower-middle class constituency is a kind of nationalist culturalism, which is a mere veil for a system of far more centralized capitalist control of the state in a White House now filled with billionaires, ultimately leading to the increased economic exploitation and expropriation of the underlying population. The material betrayal of the working class will be absolute, economically and politically. For such a regime of capitalist overlords to continue, it will have to increase its repression of the body politic at every step. Its greatest fear is that the enraged masses, especially the working-class majority, would mobilize and rise up in resistance, bringing with it all of those in the society as a whole who are committed to democratic rule and to the survival of humanity in the face of growing environmental perils.

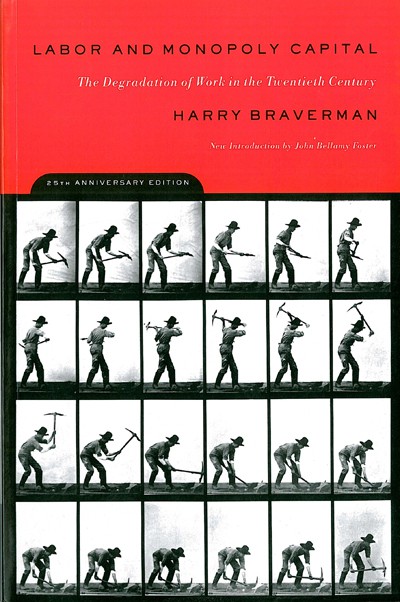

The political and ideological successes of the MAGA movement were made possible in part by a liberal-left that abandoned the working class economically and politically under the mantle of postmodernism and identity politics, severed off from questions of exploitation, poverty, and economic and social decline. This requires a return to what Marx called the “hierarchy of…needs,” emphasizing within this real material needs, including jobs, health care, housing, free human development, community, the environment, and the right to control one’s own body—needs vital to the population as a whole, and ultimately inseparable from democratic control of the society.75 Viewed in this way, the only way to combat the current reactionary trend is based on socialist principles of substantive equality and ecological sustainability, putting the needs of the population as a whole, and those most oppressed, first. This struggle will have to emanate in the main from a resurgent, reunited working class, historically the most diverse, democratic, and revolutionary section of society, the guarantors of humanity’s future.

Notes

- ↩ Matthew J. Vaeth, “Memorandum for Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies/Subject: Temporary Pause of Agency, Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs,” Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, January 27, 2025; Travis Gettys, “‘Reads Like a Hostage Note’: Trump Order Flagged as ‘Mass Fraud’ by Ex-Official,” Raw Story, January 28, 2025; Charles R. Kesler, “America’s Cold Civil War,” Imprimis47, no. 10 (October 2018).

- ↩ Vought quoted in Thomas B. Edsall, “‘Trump’s Thomas Cromwell’ Is Waiting in the Wings,” New York Times, February 4, 2025.

- ↩ For a leading MAGA proponent of “Caesarism” as constituting the inner telos of the Trump regime, see Michael Anton, The Stakes: America at the Point of No Return (Washington DC: Regnery Publishing, 2020), 303–18.

- ↩ Max Matsa, “Senate Confirms Project 2025 Co-Author as Trump Budget Chief,” BBC, February 6, 2025; Curt Devine, Casey Tolan, Audrey Ash, and Kyung Lah, “Hidden Camera Video Shows Project 2025 Co-Author Discussing His Secret Work Preparing for a Second Trump Term,” CNN, August 15, 2024; Michael Sozan and Ben Olinsky, “Project 2025 Would Destroy the U.S. System of Checks and Balances and Create an Imperial Presidency,” Center for American Progress, October 1, 2024.

- ↩ Vaeth, Memorandum, “Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs”; Melissa Quinn, Richard Escobedo, and Kristin Brown, “Trump Administration Rescinds Federal Funding Freeze Memo After Chaos,” CBS News, January 29, 2025; Daniel Barnes, Chloe Atkins, and Dareh Gregorian, “Appeals Court Rejects Trump Administration Bid to Immediately Reinstate Funding Freeze,” NBC News, February 11, 2025; Bill Barrow, “How Donald Trump and Project 2025 Previewed the Federal Grant Freeze,” Associated Press, January 28, 2025.

- ↩ Cass R. Sunstein, “This Theory Is Behind Trump’s Power Grab,” New York Times, February 26, 2025.

- ↩ Vaeth, Memorandum, “Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs.”

- ↩ Lance Cashion, “How to Recognize Cultural Marxism and Critical Theories,” Revolution of Man (blog), August 31, 2023; Mike Gonzalez and Katharine Cornell Gorka, NextGen Marxism: What It Is and How to Combat It (New York: Encounter Books, 2025), 15, 238, 265–69. The current right-wing attack on “Cultural Marxism” is derived from attacks on “Cultural Bolshevism” in Nazi Germany. Ari Paul, “‘Cultural Marxism’: The Mainstreaming of a Nazi Trope,” Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, June 4, 2019, fair.org.

- ↩ Trump/Vance Campaign, “Agenda 47: Protecting Students from the Radical Left and Marxist Maniacs Infecting Educational Institutions,” July 17, 2023.

- ↩ Mike Gonzalez and Katharine C. Gorka, How Cultural Marxism Threatens the United States—and How Americans Can Fight It, Special Report No. 262, Heritage Foundation, November 14, 2022; Gonzalez and Gorka, NextGen Marxism; Tanner Mirrlees, “The Alt-Right’s Discourse of ‘Cultural Marxism’: A Political Instrument of Intersectional Hate,” Atlantis Journal 39, no. 1 (August 2018); Cashion, “How to Recognize Cultural Marxism and Critical Theories.” All of these works are poorly researched, poorly documented, unscholarly, and shallow, not conforming to academic standards in any way. As Baruch Spinoza said, “Ignorance is no argument.”

- ↩ Gonzalez and Gorka, NextGen Marxism, 17–18, 148–99, 242.

- ↩ See John Bellamy Foster, Trump in the White House (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2017), 20–22, 121.

- ↩ For criticism of how white evangelical Christians in the United States have embraced a “slaveholder religion,” capitulating to the religious views propounded in the Antebellum South and in the Jim Crow period, see Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, Reconstructing the Gospel: Finding Freedom from Slaveholder Religion (Lisle, Illinois Inter-Varsity Press, 2020); Darrell Hamilton II, “It’s Time to Break the Chains of Slaveholder Religion,” Baptist News, September 17, 2020.

- ↩ Paul M. Sweezy to Paul A. Baran, October 18, 1952, in Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, The Age of Monopoly Capital, eds. Nicholas Baran and John Bellamy Foster (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2017), 86–87.

- ↩ Franz Neumann, Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1942); Doreen Lustig, “The Nature of the Nazi State and the Question of International Criminal Responsibility of Corporate Officials at Nuremberg: Franz Neuman’s Behemoth at the Industrial Trials,” Working Paper 2011/2, History and Theory of International Law Series, Institute for International Law and Justice, 2012; C. Wright Mills, White Collar: The American Middle Classes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951), 350–54. On the lower-middle class/monopoly capitalist alliance in societies belonging to the fascist genus, see also Leon Trotsky, The Struggle Against Fascism in Germany (New York: Pathfinder, 1971), 455; Ernst Bloch, Heritage of Our Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 54; Nicos Poulantzas, Fascism and Dictatorship (London: Verso, 1974); Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man (New York: Doubleday, 1960), 134–76; Paul A. Baran (Historicus), “Fascism in America,” Monthly Review 4, no. 6 (October 1952): 181–89.

- ↩ Maxine Y. Sweezy (see also Maxine Y. Woolston), The Structure of the Nazi Economy(Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1941), 27–35; Gustave Strolper, German Economy, 1870–1940 (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1940), 207; Germá Bel, “The Coining of ‘Privatization’ and Germany’s National Socialist Party,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, no. 3 (2006): 187–94; Foster, Trump in the White House, 27–43, 65–66.

- ↩ Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (London: Penguin, 2017); Reuven Kaminer, “On the Concept of ‘Totalitarianism’ and Its Role in Current Political Discourse,” MR Online, August 15, 2007; Slavoj Žižek, Did Somebody Say Totalitarianism? (London: Verso, 2001), 2–3.

- ↩ Baran, “Fascism in America,” 182.

- ↩ Georg Lukács, Writer and Critic (London: Merlin Press, 1978), 151.

- ↩ Christopher Caldwell, “Speaking Trumpian,” Claremont Review of Books 24, no. 19 (Fall 2024): 19–22.

- ↩ Andy Kroll, “Revealed: The Billionaires Funding the Coup’s Brain Trust,” Rolling Stone, January 12, 2022; Influence Watch, “Thomas D. Kligenstein Fund,” influencewatch.org (n.d.).

- ↩ Georg Lukács, The Destruction of Reason (London: Merlin Press, 1980), 730. Lukács’s reference to Carlyle here is directly relevant to the present. Leading MAGA ideologue Curtis Yarvin writes: “I will always be a Carlylean, just the way a Marxist will always be a Marxist.” Matt McManus, “Yarvin’s Case against Democracy: Curtis Yarvin Is too Elitist for Fascism,” Commonweal, January 27, 2023.

- ↩ Marc Fisher and Isaac Stanley-Becker, “The Claremont Institute Triumphed in the Trump Years. Then Came Jan. 6,” Washington Post, July 30, 2022; Elisabeth Zerofsky, “How the Claremont Institute Became a Nerve Center of the American Right,” New York Times, August 3, 2022; Kroll, “Revealed.”

- ↩ Kate Brannen and Luke Hartig, “Disrupting the White House: Peter Thiel’s Influence is Shaping the National Security Council,” Just Security, February 8, 2017.

- ↩ Michael Anton, “The Flight 93 Election,” Claremont Review of Books (online), September 5, 2016.

- ↩ Michael Anton, After the Flight 93 Election: The Vote that Saved America and What We Still Have to Lose (New York: Encounter Books, 2019); Anton, The Stakes: America at the Point of No Return (see especially section on “Caesarism” in chapter 7 and the sections on “Immigration,” “Reelect Trump!” and on “Foreign and Defense Policy” in chapter 8.

- ↩ Michael Anton, “Draining the Swamp,” Claremont Review of Books, 19, no. 1 (Winter 2018/19).

- ↩ Anton, “Draining the Swamp.”

- ↩ Michael Anton, “Are the Kids Al(t) Right?,” Claremont Review of Books 19, no. 3 (Summer 2019). On Nietzsche’s “last man” see Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra (New York: Modern Library, 1917), 10–13 (prologue, section 5).

- ↩ Bronze Age Pervert (Costin Vlad Alamariu), Bronze Age Mindset (self-published, 2018), 12, 14, 40, 44, 52, 56, 72, 76, 80, 84, 92, 104, 110, 112–14, 118, 120–22, 126, 132–36; Ben Schreckinger, “The Alt-Right Manifesto that has Trumpworld Talking,” Politico, August 23, 2019; BAP quoted on fascism in Ali Breland, “Is the Bronze Age Pervert Going Mainstream?,” Mother Jones, October 2, 2023; Sophie Nicolson, “Bob Denard: French Mercenary Behind Several Post-Colonial Coups,” Guardian, October 15, 2007.

- ↩ Jason Wilson, “He’s Anti-Democracy and Pro-Trump: The Obscure ‘Dark Enlightenment’ Blogger Influencing the Next US Administration,” Guardian, December 21, 2024; Ian Ward, “Curtis Yarvin’s Ideas Were Fringe. Now They’re Coursing through Trump’s Washington,” Politico, January 30, 2025; Ian Ward, “The Seven Thinkers and Groups that Have Shaped JD Vance’s Unusual Worldview,” Politico, July 18, 2024; Jacob Siegel, “The Red-Pill Prince: How Computer Programmer Curtis Yarvin Became America’s Most Controversial Political Theorist,” The Tablet, March 30, 2022; Curtis Yarvin interviewed by David Marchese, “Curtis Yarvin Says Democracy Is Done. Powerful Conservatives Are Listening,” New York Times, January 18, 2025; “Curtis Yarvin (Mencius Moldbug) on Tucker Carlson Today,” YouTube video, 1:15:35, September 8, 2021,

- ↩ Jeremy Carl, “Beyond Elves and Hobbits,” The American Mind, July 22, 2022; McManus, “Yarvin’s Case against Democracy.”

- ↩ Wilson, “He’s Anti-Democracy and Pro-Trump”; Ward, “Curtis Yarvin’s Ideas Were Fringe”; Ward, “The Seven Thinkers and Groups that Have Shaped JD Vance’s Unusual World View”; Curtis Yarvin, “The Cathedral or the Bizarre,” The Tablet, March 30, 2022; Curtis Yarvin, “The Nihilism of the Ruling Class,” Compact, December 16, 2022. On the classical notion of oligarchy, see Jeffrey A. Winters, Oligarchy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- ↩ Michael Anton, “The Pessimistic Case for the Future,” Compact, July 21, 2023.

- ↩ Christopher F. Rufo, “Critical Race Theory: What It Is and How to Fight It,” Imprimis 50, no. 3 (March 2021).

- ↩ Christopher F. Rufo, “Laying Siege to the Institutions,” Imprimis 51, no. 4/5 (April/May 2022); Christopher F. Rufo, “Inside the Transgender Empire,” Imprimis 52, no. 9 (September 2023); Scott Yenor, “Repeal and Replace Today’s Education Cartel,” Law & Liberty, March 28, 2024, lawliberty.org; Frederick M. Hess, “Challenge the College Cartel,” The American Mind, July 2, 2019; Giancarlo Sopo, “Trump Must Break Up the College Cartel,” The American Mind, December 6, 2024.

- ↩ Christopher Caldwell, “The Browning of America,” Claremont Review of Books 15, no. 1 (Winter 2014/15); Christopher Caldwell, “There Goes Robert E. Lee,” Claremont Review of Books21, no. 2 (Spring 2021).

- ↩ Kesler, “America’s Cold Civil War.”

- ↩ Brian T. Kennedy, “Facing Up to the China Treat,” Imprimis 49, no. 9 (September 2020).

- ↩ Ali Breland, “Charlie Kirk Doesn’t Really Seem to Mind White Nationalism,” Mother Jones, February 13, 2024; Robert Draper, “How Charlie Kirk Became the Youth Whisperer of the American Right,” New York Times, February 10, 2025; Charlie Kirk, Right-Wing Revolution: How to Beat the Woke and Save the West (Lewes, Delaware: Winning Team Publishing, 2024); Foster, Trump in the White House, 40.

- ↩ Mike Hixenbaugh and Allan Smith, “Charlie Kirk Once Pushed a ‘Secular Worldview.’ Now He’s Fighting to Make America Christian Again,” NBC News, June 12, 2024.

- ↩ Russell Vought, “Renewing American Purpose,” The American Mind, September 29, 2022; U.S. Constitution, Art. 1, Sect. 10, Cl. 3.

- ↩ Center for Renewing America Staff, “Primer: Palestinian Culture is Prohibitive for Assimilation,” Center for Renewing America, December 1, 2023; Miles Bryan, “The Christian Nationalist Legal Scholar Behind Trump’s Purges: Russell Vought and His Racial Philosophy Explained,” Vox, February 20, 2025.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster, The Return of Nature (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020), 263–64.

- ↩ Matt McManus, “Social Democracy and Social Conservatism Aren’t Compatible,” Jacobin, August 22, 2023.

- ↩ On Žižek, see Gabriel Rockhill, “Capitalism’s Court Jester: Slavoj Žižek,” Counterpunch, January 2, 2023.

- ↩ See Michael Anton, “America Against the Deep State,” Compact, September 16, 2022; Christopher Rufo, “What Conservatives See in Hungary,” Compact, July 28, 2023; Christopher Caldwell, “Germany Considers the Alternative,” Compact, February 10, 2025. In a curious statement, Žižek wrote: “I love Compact for a simple reason: because it’s precisely not compact—it is a battlefield of ideas in conflict with each other. Only in this way can something new emerge today.” In fact, Compact is a publication where the MAGA philosophy is hegemonic, and which includes some former leftists moving right.

- ↩ Christian Parenti, “The Left Case for Kash Patel,” Compact, December 31, 2024; Christian Parenti, “Why RFK Must Take on the CIA,” Compact, December 11, 2024; Christian Parenti, “Diversity is a Ruling-Class Ideology,” Compact, January 19, 2023; Christian Parenti, “Trump’s Real Crime is Opposing Empire,” Compact, April 7, 2023; Christian Parenti, “The Left-Wing Origins of the ‘Deep State’ Theory,” Compact, February 28, 2025. Aside from the contradictory nature of an argument that sees Trump as the enemy of the deep state, this concept, which played so centrally in the Trump I administration, has been largely dropped in MAGA ideology as self-defeating, while Trump II has focused on slashing the administrative state.

- ↩ Slavoj Žižek, “Wokeness Is Here to Stay,” Compact, February 22, 2023; Vincent Lloyd, “A Black Professor Trapped in an Anti-Racist Hell,” Compact, February 10, 2023; Melanie Zelle, “Žižek Has Lost the Plot,” The Phoenix (Swarthmore College), March 2, 2023.

- ↩ Geoff Shullenberger, “What BAP Learned from Feminism,” Compact, September 22, 2023; Geoff Schullenberger, “The Philosophy of Bronze Age Pervert,” Mother Maiden Matriarch with Louise Perry, Episode 35, October 15, 2023; Elena Louisa Lange and Geoff Shullenberger, COVID-19 and the Left: The Tyranny of Fear (London: Routledge, 2024).

- ↩ Allum Bokhari, “Who Is in Control?: The Need to Rein in Big Tech,” Imprimis 50, no. 1 (January 2021).

- ↩ Rosie Gray, “Breitbart’s Raheem Kassam Is Out: The Editor of Site’s London Bureau Was One of the Last Steve Bannon Allies Left within the Organization,” The Atlantic, May 23, 2018; “The National Pulse’s Kassam: How Did America Fall to Marxism?,” Grabien, June 6, 2020; Batya Ungar-Sargon, Bad News: How Woke Media is Undermining Democracy (New York: Encounter Books, 2021).

- ↩ Amanda Crocker, “F*ck Big Book,” Canadian Dimension, February 20, 2025.

- ↩ Anton, After the Flight 93 Election; Charles R. Kesler, Crisis of the Two Constitutions: The Rise, Decline, and Recovery of America’s Greatness (New York: Encounter Books, 2021); Brian T. Kennedy, Communist China’s War Inside America (New York: Encounter Books, 2020); Kirk, Right Wing Revolution. Peter Collier, the founder of Encounter Books, was a former leftist and coeditor of Ramparts magazine along with David Horowitz, when they uncovered Encountermagazine’s CIA funding. He afterward moved to the far (together with Horowitz).

- ↩ Jesse Watters quoted in David Siroto, “How to Combat the Information War,” The Lever, February 24, 2025, levernews.com.

- ↩ Steve Bannon, “America’s Great Divide: Interview with Steve Bannon,” PBS Frontline, March 17, 2019; Michael Anton, “Why the Great Reset Is Not ‘Socialism,’” Compact, November 30, 2022; Foster, Trump in the White House, 32–33, 72; Steve Inskeep, “Steve Bannon Says MAGA Populism Will Win—as Trump Is Surrounded by Billionaires,” NPR, January 19, 2025; Jeremy Carl, “Beyond Elves and Hobbits,” The American Mind, July 22, 2022.

- ↩ Anton, “Why the Great Reset Is Not ‘Socialism.’”

- ↩ On the lower-middle class basis of the MAGA movement, see Foster, Trump in the White House, 19–21, 63; Les Leopold, “The Myth of MAGA’s Working Class Roots,” UnHerd, February 16, 2024; Dennis Gilbert, The American Class Structure in an Age of Growing Inequality (Los Angeles: Sage, 2011), 14, 243–47; David Doonan “Alienated, Not Apathetic: Why Workers Don’t Vote,” Green Party US, August 5, 2019, gp.org; Phil A. Neel, Hinterland: America’s New Landscape of Class and Class Conflict (London: Reaction Books, 2018), 36–37. There are of course no hard lines between the working class and the lower-middle class or petty bourgeoisie. Not income and property alone, but also urban/rural divisions and education play a role in the determination of classes in the political sense. The lower-middle class is far more significant politically than it is demographically because of its higher voter turnout when compared to the working class.

- ↩ Taylor Popielarz, “An Old Steel Town Highlights How West Virginia Went from Deeply Blue to Trump Country,” Spectrum News NY1, May 24, 2024.

- ↩ Anton, “Why the Great Reset Is Not ‘Socialism.’”

- ↩ Karl Dietrich Bracher, “Stages of Totalitarian ‘Integration’ (Gleichschaltung): The Consolidation of National Socialist Rule in 1933 and 1934,” in Republic to Reich, ed. Hajo Holborn (New York: Vintage, 1972), 124–28; Foster, Trump in the White House, 25–29.

- ↩ Gary Stout, “The Marriage of MAGA and Billionaires Is Already Rocky,” Observer-Reporter, January 25, 2025.

- ↩ Steve Inskeep, “Steve Bannon Says MAGA Populism Will Win—as Trump Is Surrounded by Billionaires”; Rana Foroohar, “MAGA vs. the Billionaires,” Financial Times, January 5, 2005; Nia-Malika Henderson, “Trump Inauguration: Old MAGA vs. New MAGA’s Cage Match Begins,” Bloomberg, January 20, 2025; Thomas D. Williams, “Steve Bannon: I Will Do Anything’ to Keep Elon Musk Out of the White House,” Breitbart, January 11, 2025.

- ↩ Kevin Porteus, “Putting Americans First,” The American Mind, January 8, 2025.

- ↩ Vivek Ramaswamy, Woke, Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam (New York: Center Street, 2023); Steve Rattner, “What Big-Business Leaders, Including Democrats, Say Privately About Trump,” New York Times, March 3, 2025.

- ↩ Peter Thiel interviewed by Peter Robinson, “Peter Thiel, Leader of the Rebel Alliance,” Uncommon Knowledge Podcast, Hoover Institution, November 9, 2022.

- ↩ Peter Thiel, “The Education of a Libertarian,” Cato Unbound, April 13, 2009.

- ↩ Max Chafkin interviewed by Belinda Luscombe, “Who’s Afraid of Peter Thiel?: A New Biography Suggests We All Should Be,” Time, September 21, 2021; Deborah Veneziale, “Trump’s Nationalist Conservative White Christian Agenda,” MR Online, February 28, 2025; Jessica Matthews, “How Peter Thiel’s Network of Right-Wing Techies Is Infiltrating Donald Trump’s White House,” Fortune, January 17, 2025; Brannen and Hartig, “Disrupting the White House.”

- ↩ Rob Larson, Mastering the Universe (Chicago: Haymarket, 2024), xi.

- ↩ Ed Kilgore, “”Trump is Dividing Evangelicals Now, Too,” New York Magazine, February 13, 2025; Sam R. Schmitt, “‘Give Cheerfully, Give Abundantly’: White American Prosperity Evangelism, Financial Obedience, and Religious Corruption in the Trump Era,” Activist History Review, May 11, 2018; James Bohland, “The Truth About MAGA: Plutocrats in Populist Clothing,” Fair Observer, October 29, 2024; Jessica Washington, “How Trump Twisted DEI to Only Benefit White Christians,” The Intercept, February 22, 2023.

- ↩ Wilson-Hartgrove, Reconstructing the Gospel, 33–35; Hamilton, “It’s Time to Break the Chains of Slaveholder Religion.”

- ↩ Jonathan Wilson-Hargrove, “In the Age of Trump, a Moment of Decision for Evangelicals,” Durham Herald Sun, April 26, 2018.

- ↩ Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, “Fear Is the Slaveholder Religion’s Tool of Control,” Sojourners, April 22, 2019.

- ↩ Sharon Parrott, “Well, That Was Quick: Trump’s Total Betrayal of Working People Is Now Complete,” Common Dreams, February 26, 2025.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Texts on Methods (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1975), 195.