“The Contagion of Capital: Financialized Capitalism, COVID-19, and the Great Divide” (coathored with R. Jamil Jonna and Brett Clark, Foster listed first), Monthly Review, vol. 72 no. 8 (January 2021), pp. 1-19.

The authors thank John Mage, Craig Medlen, and Fred Magdoff for their assistance.

The U.S. economy and society at the start of 2021 is more polarized than it has been at any point since the Civil War. The wealthy are awash in a flood of riches, marked by a booming stock market, while the underlying population exists in a state of relative, and in some cases even absolute, misery and decline. The result is two national economies as perceived, respectively, by the top and the bottom of society: one of prosperity, the other of precariousness. At the level of production, economic stagnation is diminishing the life expectations of the vast majority. At the same time, financialization is accelerating the consolidation of wealth by a very few. Although the current crisis of production associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has sharpened these disparities, the overall problem is much longer and more deep-seated, a manifestation of the inner contradictions of monopoly-finance capital. Comprehending the basic parameters of today’s financialized capitalist system is the key to understanding the contemporary contagion of capital, a corrupting and corrosive cash nexus that is spreading to all corners of the U.S. economy, the globe, and every aspect of human existence.

Free Cash and the Financialization of Capital

“Capitalism,” as left economist Robert Heilbroner wrote in The Nature and Logic of Capitalism in 1985, is “a social formation in which the accumulation of capital becomes the organizing basis for socioeconomic life.”1 Economic crises in capitalism, whether short term or long term, are primarily crises of accumulation, that is, of the savings-and-investment (or surplus-and-investment) dynamics. Investment in new productive capacity in new or existing businesses is what determines growth. Such investment decisions are governed by expected profits on new investments.

Viewed in these terms, the decline in the long-term growth rate experienced by the mature, monopolistic economies of the United States, Europe, and Japan over the last half century can be seen as related principally to the atrophy of net investment.2 Existing excess capacity in plant and equipment, a product of the monopolistic structure of accumulation, tends to decrease expected profits on new investment.3 The U.S. economy has seen a long-term decline in capacity utilization in manufacturing, which has averaged 78 percent from 1972 to 2019—well below levels that stimulate net investment.4 As a result, the capital accumulation process within production has stagnated, with existing idle capacity tending to shut off the creation of new capacity. From 1960 to 1980, it was common for private net investment to constitute around 40 percent of private gross investment. Since 2000, this has dropped to around 20 percent, even as gross investment has weakened relative to national income.5

The significance of the atrophy of net investment in the core capitalist countries cannot be exaggerated. As the foremost emerging economy in the world today, China has what economist Zhun Xu calls a “high Baran ratio,” standing for investment as a share of economic surplus. Conceptually, economic surplus—the difference between national output and wage income or essential consumption—is gross property income (profit, rent, interest). Zhun uses the income of the top 10 percent as a proxy for economic surplus. On this basis, he explains, China has invested around 80 percent of its economic surplus, leading to high growth rates of 7 percent or higher. In contrast, mature, monopolistic economies such as the Group of 7 (the United States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Canada) typically have relatively low Baran ratios, investing less than 50 percent of economic surplus, resulting in what for decades have been weak and declining average annual growth rates.6

Given these conditions, it is important to ask: What happens to that part of the economic surplus held by corporations and individual capitalists that is not invested in new capacity?7Some of it is used for capitalist consumption, but this has inherent limits. The vast economic surplus (actual and potential) generated by the system of economic exploitation far exceeds what can be spent in the luxury consumption of the wealthy, however ostentatious. More importantly, capitalists do not desire to consume the larger part of the economic surplus at their disposal, since, above all else, they seek to amass wealth.

Government spending absorbs some of the economic surplus, as does waste in the business process. However, government deficit spending also increases corporate profits after taxes above the level determined by capitalist spending on consumption and investment.8 Hence, with both the growth of the federal deficit and the stagnation of investment, the amount of free cash in corporate coffers has dramatically expanded. This free cash plays a central role in the financialization of capital and the resulting extreme polarization of society.9

As stipulated by Craig Medlen in Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, free cash equals corporate profits after taxes plus depreciation minus investment. (In national income accounting, corporate profits after taxes plus depreciation is known as corporate cash flow. The funds associated with depreciation [or capital consumption] are part of the gross surplus available to corporations.)10

A wider conception of free cash, utilized in this article, also includes net interest. Hence, in the wide version, Free Cash = Corporate Profits After Taxes + Depreciation + Net Interest – Investment.11 This free cash is held by corporations or is distributed to stockholders through dividend payouts and/or stock buybacks.12

Building on the research of Michał Kalecki, Medlen demonstrates that the amount of free cash is identical to the federal government deficit minus the excess of savings over investment of the noncorporate sector (now usually negative) plus the current account balance. The three factors of (1) the federal deficit, (2) the country’s current account balance (or the trade deficit), and (3) the deficit spending of the noncorporate sector (encompassing noncorporate business, housing, and personal finance) can therefore be seen as underpinning free cash.13

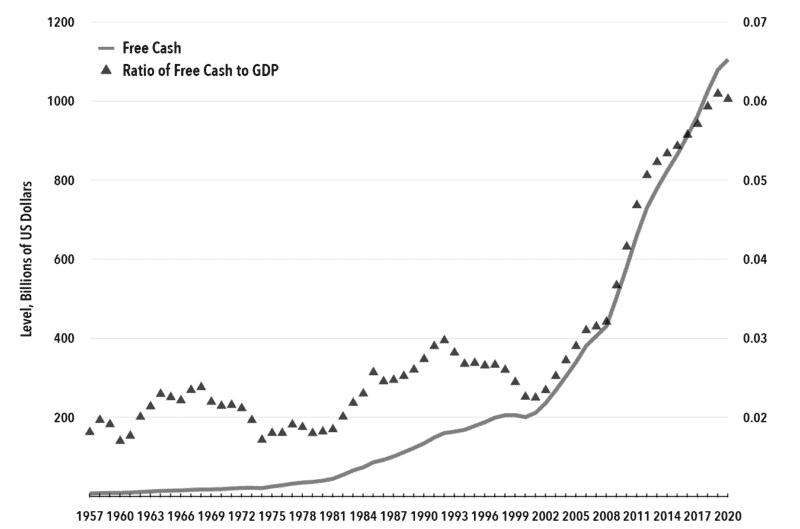

Chart 1 shows the growth of corporate free cash in the U.S. economy from the period immediately after the Second World War to the present. Free cash, as non-invested surplus, became a much bigger and bigger factor in the U.S. economy beginning in the 1980s due mainly to the combined effects of a long-term decline in corporate taxation, the increasing federal deficit, and the atrophy of net investment.14 Free cash falls in recessions (due to lower business activity and income), but then rockets up soon afterward due to investment not keeping up with increasing economic activity, freeing up more cash after investment. This sudden rebound in cash is also a product of the fact that the Federal Reserve Board now steps in during every recession, at precisely such “Minsky Moments” when the prospects for investment are at their worst, with lavish provision of low-interest credit.

Chart 1. Free Cash, U.S. Corporations, 1957-2019 (5-year Moving Average)

Notes: Free Cash is calculated as the sum of Corporate Profits after tax (W273RC1Q027SBEA), Depreciation (CCFC), and Net Interest (A453RC1Q027SBEA) minus Corporate Fixed Investment, which includes investment in nonresidential structures (FBGFEEQ027S and BOGZ1FA105013005Q), residential structures (BOGZ1FA105012005Q), and inventories (NCBIAVQ027S). The ratio divides by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Quarterly data reported as 5-year moving averages.

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.14. Gross Value Added of Domestic Corporate Business and Federal Reserve (Financial Accounts); Table F.2 Distribution of Gross Domestic Product. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 16, 2020, fred.stlouisfed.org. Series IDs corresponding to FRED variables are included above in parentheses.

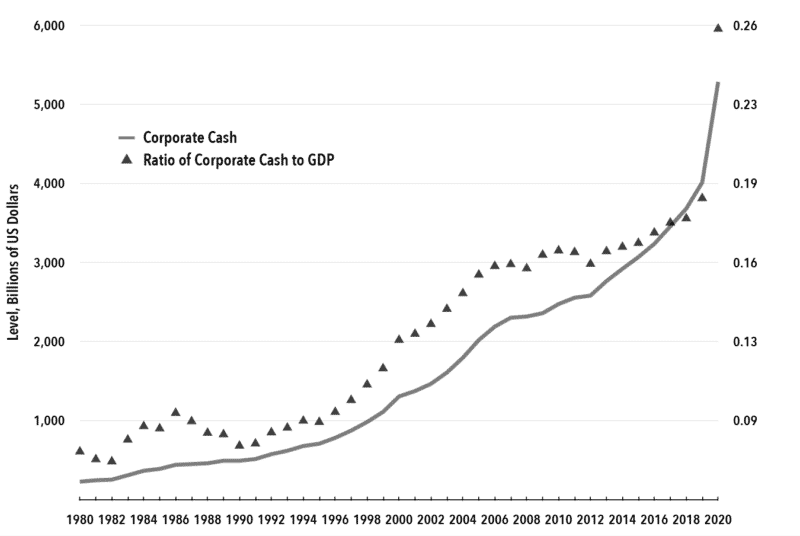

Another way of looking at this phenomenon is to chart the total cash or liquid funds that corporations actually have ready at hand, if they were to choose to invest (or otherwise productively use) the surplus at their disposal. Of course, corporate investment is not dependent on the prior availability of savings/surplus, since capitalism, as Joseph Schumpeter long ago explained, is a system that creates “credit ad hoc”; while John Maynard Keynes and Kalecki taught that investment determines savings, not the other way around.15 Nevertheless, it is significant that the cash funds of corporations in the current phase of monopoly-finance capital far exceed profitable investment outlets. At the beginning of 2020, nonfinancial corporations were sitting on over $4 trillion dollars in cash; before the end of 2020 this had risen to over $5 trillion.16 According to the Federal Reserve Flow of Funds data, shown in Chart 2, total cash held by U.S. nonfinancial corporations as a share of gross domestic product (GDP)—much of it parked abroad in tax havens—has almost tripled between the early 1990s and the present.17

Chart 2. Cash On-Hand, U.S. Nonfinancial Corporations, 1980-2020 (5-year Moving Average)

Notes: Corporate Cash is the sum of lines 1-7 of Table L.102 Nonfinancial Business from Financial Accounts of the United States. Data points are reported as 5-year moving averages.

Source: Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 16, 2020, https://fred.stlouisfed.org. Series IDs: FDABSNNCB, BOGZ1FL143020005Q, BOGZ1FL143030005Q,BOGZ1FL143034005Q, SRPSABSNNCB, BOGZ1FL144022005Q, and GDP.

The total cash holdings of nonfinancial corporations on hand at any given time are not to be confused with free cash, which is that part of the corporate cash flow left over after investment in a given year—much of which is not held as cash deposits but instead spent on mergers and acquisitions, stock buybacks, and other financial instruments. Rather, total cash on hand, as defined by the Federal Reserve Flow of Funds, simply measures the actual cash deposits sitting in the accounts of nonfinancial corporations presented as annual averages based on quarterly data. Still, the rapid growth of total cash currently held by nonfinancial corporations in the form of ready monies, both absolutely and as a proportion of GDP (as shown in Chart 2), is a further indication of an economy that has shifted from capital formation to speculation.

As we have seen, when corporations do not invest their economic surplus in new capital formation—primarily due to vanishing investment opportunities in an economy characterized by excess capacity—they are left with abundant free cash that is partly returned to the shareholders through share buybacks and, to a lesser degree, dividends. It is also used for speculation, including mergers, acquisitions, and the panoply of corporate “cash management” techniques that amount to the leveraging of free cash to enhance returns.18 This gives rise to a whole alphabet soup of financial instruments, in which corporations use the cash at their disposal partly as collateral for debt leverage, with nonfinancial corporate debt rising rapidly as a share of national income. Predictably recurring internal corporate funds in the form of free cash constitute a “flow collateral” allowing for further leverage, feeding speculation. A speculative economy relies on borrowed funds for leverage, backed up in part by cash. Expanding cash reserves are also needed as hedges in case of financial defaults. The whole system is a house of cards.

The progressive financialization of the capitalist economy, whereby the financial superstructure continues to expand as a share of the underlying productive economy, has led to ever-greater asset price bubbles and growing threats of world economic meltdown. So far, a complete meltdown has been headed off by central banks, as in the 2000 and 2008 financial crashes. At every major recurring disturbance, and with serious economic repercussions, the monetary authorities pump massive amounts of cash into the financial superstructure of the economy only to give rise to greater bubbles in the future.

Theoretically, stock values represent future expected streams of earnings arising primarily from production.19 Nowadays, however, finance has become increasingly autonomous from production (or the “real economy”), relying on its own speculative “self-financing,” leading to financial bubbles, contagions, and crashes, with the monetary authorities intervening to keep the whole house of cards from collapsing. This serves to reduce the risk to speculators, thereby keeping the value of stocks and other financial assets rising on a long-term basis, along with the overall wealth/income ratio. In these circumstances, so-called asset accumulation by speculative means has replaced actual accumulation or productive investment as a route to the increase of wealth, generating a condition of “profits without production.”20

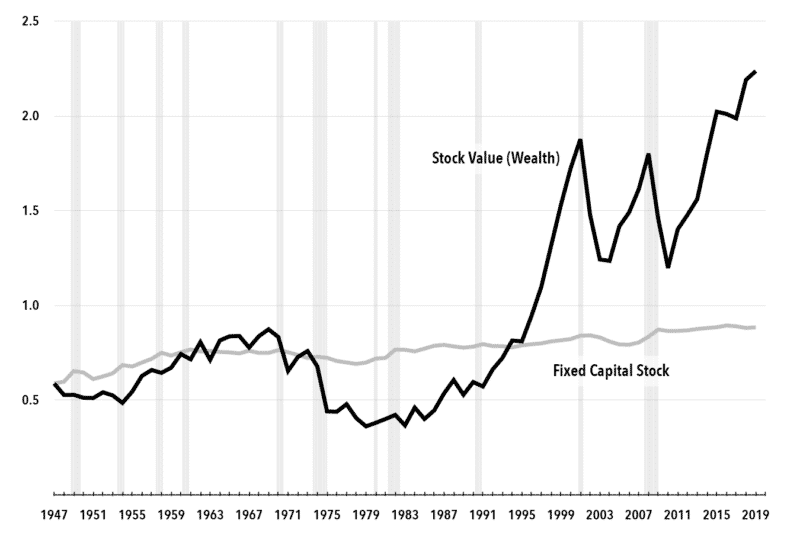

In order to grasp the full significance of the financialization of the economy, it is useful to look at the two conceptions of capital (relative to national income) depicted in Chart 3.21 One of these, the numerator of the lower line, is the traditional conception of capital as fixed investment stock (physical structures and equipment) at historical cost minus depreciation. This is called the fixed capital stock of the nation and is tied directly to economic growth.22 It represents what economic theorists from Adam Smith to Karl Marx to Keynes have referred to as the accumulation of capital. Capital formation and national income are closely related, generally rising and falling together, producing the relatively flat line, representing the ratio of fixed capital stock to national income, shown in Chart 3.

Chart 3. Capital and Wealth to Income Ratios, U.S., 1947-2019

Note: Grey bars indicate economic recession periods (USREC).

Sources: Fixed Capital Stock: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 4.3. Historical-Cost Net Stock of Private Nonresidential Fixed Assets by Industry Group and Legal Form of Organization. Stock Value: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, retrieved November 16, 2020, https://fred.stlouisfed.org. Series IDs: BOGZ1FL893064105Q (All Sectors; Corporate Equities; Asset, Level) and GDP.

Yet, capital, as Marx noted very early in the process, has more and more taken on the “duplicate” form of “fictitious capital,” that is, the structure of financial claims (in monetary values) produced by the formal title to this real capital. Insofar as economic activity is directed to the appreciation of such financial claims to wealth relatively independently of the accumulation of capital at the level of production, it has metamorphosed into a largely speculative form.23

This can be seen by looking again at Chart 3. In contrast to the lower line, the upper line depicts what is traditionally seen as the wealth/income ratio (which some economic theorists, such as Thomas Piketty, conflate with the capital/income ratio, treating wealth as capital).24 The numerator here is the value of corporate stocks. Since the mid–1980s, the ratio of stock value to national income has increased more than 300 percent. This marks an enormous growth of financial wealth, with speculation-induced asset growth sidelining the role of productive investment or capital accumulation as such in the amassing of wealth. This is associated with a massive redistribution of wealth to the top of society. The top 10 percent of the U.S. population owns 88 percent of the value of stocks, while the top 1 percent owns 56 percent.25Rising stock values relative to national income thus mean, all other things being equal, rapidly rising wealth (and income) inequality.26

The existence of the two conceptions of capital (and of capital/income ratios) presented here—one representing historical investment cost minus depreciation, and conforming to the notion of accumulated capital stock, the other the monetary value of stock equities (in economics traditionally treated as wealth rather than capital)—is often downplayed within establishment economics under the assumption that in the long run they will simply fall in line with each other, and with national income. As leading mainstream economic growth theorist Robert Solow writes: “Stock market values, the financial counterpart of corporate productive capital, can fluctuate violently, more violently than national income. In a recession the wealth-income ratio may fall noticeably, although the stock of productive capital, and even its expected future earning power, may have changed very little or not at all. But as long as we stick to longer-run trends…this difficulty can safely be disregarded.”27

But can the divergence of stock values from income (and from fixed capital stock) in reality be so easily disregarded? Chart 3 depicts a sharp increase in stock values relative to national income, which has now continued for over a third of a century, with decreases in total stock values as a ratio of national income (output) occurring during recessions, then rebounding during recoveries.28 The overall movement is clearly in the direction of compounded financial hyperextension. This conforms to the general pattern of the financialization of the capitalist economy, constituting a structural change in the system associated with the growth of monopoly-finance capital. This has gone hand in hand with a bubblier economy, with financial bubbles bursting in 1987, 1991, 2001, and 2008, but ultimately shored up by the Federal Reserve and other central banks.

Today, vast amounts of free cash are spilling over into waves of mergers and acquisitions, typically aimed at acquiring megamonopoly positions in the economy. A major focus is the tech sector, much of which is directed at commodifying all information in society, in the form of a ubiquitous surveillance capitalism.29 All financial bubbles derive their animus from some common rationale, which claims that this time is different, discounting the reality of a bubble. In the present case, the rationale is that the advance of the FAANG stocks (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google), which now comprise almost a quarter of the value of Standard and Poor 500’s total capitalization, is unstoppable, reflecting the dominance of technology. Apple alone has reached a stock market valuation of $2 trillion. All of this is feeding a massive increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States, as the gains from financial assets rise relative to income. Yet, like all previous bubbles, this one too will burst.30

Kalecki determined that the export surplus on the U.S. current account increased free cash, as did the federal deficit.31 However, the current account deficit cannot be seen, in today’s overall structural context, as simply reducing free cash, because of the changed role of multinational corporations in late imperialism, which alters other parts of the equation. Due to globalization and the rise of the global labor arbitrage, U.S. multinational corporations in their intrafirm relations have in effect substituted production overseas by their affiliates for parent company exports, thereby decreasing their investment in fixed capital in the United States.32 The sales abroad of goods by majority-owned affiliates of U.S. multinational corporations in 2018 were 14.5 times the exports of goods to majority-owned affiliates.33 Foreign profits of U.S. corporations as a proportion of U.S. domestic corporate profits rose from 4 percent in 1950 to 9 percent in 1970 to 29 percent in 2019. This mainly reflects the shift in production to low unit labor cost countries in the Global South. Samir Amin described the vast expropriation of surplus from the Global South, based on the global labor arbitrage, as a form of “imperialist rent.”34

This expansion of global labor-value chains is also associated with an epochal increase in what is called the non-equity mode of production, or arm’s length production. Companies like Apple and Nike rely not on foreign direct investment abroad, but instead draw on subcontractors overseas to produce their goods at extremely low unit labor costs, often generating gross profit margins on shipping prices on the order of 50 to 60 percent.35

The loss of investment in the United States, as U.S. multinational corporations have substituted production overseas, coupled with the growth of foreign profits of U.S. megafirms, has further increased the free cash at the disposal of corporations (even with a growing deficit in the current account), thereby intensifying the all-around contradictions of overaccumulation, stagnation, and financialization in the U.S. economy. Much of this free cash is parked in tax havens overseas to escape U.S. taxes.36

Washington uses its printing press, through the federal deficit, to compensate for the U.S. current account deficit. Foreign governments cooperate, providing the “giant gift” of accepting dollars in lieu of goods, thereby acquiring massive dollar reserves.37 At some point, however, these contradictions are bound to undermine the hegemony of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, with dire ramifications for the U.S.-based world empire.

The COVID-19 Crisis and the Great Divide

Received economic ideology, with its compartmentalized view, treats the COVID-19 pandemic as simply an external shock to the economy emanating from the natural environment and thus unrelated to capitalism. However, as Rob Wallace and his colleagues have shown, contagions like COVID-19 arise from the worldwide circuits of capital associated with the global labor arbitrage and the accelerated extraction of the planet’s resources.38 This is tied especially to global agribusiness, which displaces, often forcibly, subsistence farmers while advancing into wilderness areas, destroying ecosystems, and disrupting wildlife. The result is a growing spillover of zoonoses (or diseases from other animals that are capable of being transmitted to human populations). From the standpoint of the Structural One Health tradition in epidemiology, the COVID-19 pandemic can therefore be seen as part of the larger planetary ecological crisis or metabolic rift engendered by twenty-first-century capitalism.39

In March 2020, the U.S. stock market saw a sharp dip as COVID-19 spread in the United States. The Federal Reserve immediately brought out its firehose to flood the market with liquidity, purchasing, from March to June 2020, $1.6 trillion in U.S. Treasuries and $700 billion in mortgage-backed securities, and letting markets know that there was virtually no limit to the trillions that they were ready to pour into markets.40 The result was that—just as social distancing and lockdowns were being instituted and unemployment was soaring to the highest levels since the Great Depression, reaching almost seventeen million—the U.S. stock market experienced its biggest increase since 1974 in the week of April 6 to 10.41 Wall Street profits rose in the first half of 2020 by 82 percent over the year before.42 The total wealth of U.S. billionaires skyrocketed by $700 billion between March and July 2020, even as the number of those dying from COVID-19 in the United States continued to mount and as millions of U.S. workers found themselves hit hard by the crisis.43 Amazon centi-billionaire Jeff Bezos experienced an increase in his total wealth by more than $74 billion in 2020, while Tesla megacapitalist Elon Musk saw his wealth increase in 2020 by $76 billion, making him too a centi-billionaire. (For comparison, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits provided by the federal government in Fiscal Year 2019, aiding tens of millions of low-income families, seniors on fixed incomes, and disabled people, amounted to $62.3 billion.)44 All of this points to the continuing operation of what Marx termed “the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation,” polarizing wealth and poverty, or what Solow, commenting on the work of Piketty, calls “the rich-get-richer dynamic.”45

The wreckage inflicted on the U.S. population as a whole has been enormous. In mid–October 2020, more than 25 million workers in the United States were hurt in the pandemic crisis. According to official unemployment figures, 11.1 million workers in the United States were officially unemployed; another 3.1 million had lost their jobs but were misclassified as a result of the lockdowns; 4.5 million had dropped out of the labor force since the pandemic; and 7 million were still employed but experiencing cuts in pay and hours due to the coronavirus crisis. The number claiming unemployment compensation in all programs in October equaled 21.5 million people.46 Millions are behind in payments for rent, home mortgages, and student loans while food insecurity has grown from 35 million to over 50 million as a result of insufficient government help during the pandemic.47

According to the 2020 U.S. Financial Health Pulse Report, published by the U.S. Financial Network, more than two-thirds of the U.S. population at present are in a financially unhealthy condition. Of these, more than 20 percent are concerned about not having enough food, while more than a quarter are worried about their ability to pay their next month’s rent or mortgage. Ironically, the financial health of the bottom two-thirds of the population at the time the survey was completed (August 2020) was slightly improved compared to 2019 (prior to the present economic and epidemiological crisis), due to the temporary relief mainly in the form of unemployment compensation provided by the federal government in response to the pandemic.48 In the third quarter of 2020, the U.S. economy was still 3.5 percent smaller than in the fourth quarter of 2019, with tens of millions of people suffering as a result of the crisis.49

Exploiting these conditions, the richest 1 percent saw their financial assets skyrocketing as a share of national income. FAANG stocks led the way as corporations and the wealthy turned increasingly from investment to speculative outlets, focusing on the big tech monopolies. By October 2020, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google had seen the value of their shares rise year-to-date by 29, 61, 77, 64, and 61 percent respectively.50

Such frenetic speculation naturally carries with it the growing danger of a financial meltdown. At present, the U.S. economy is faced with a stock market bubble that is threatening to burst. Two of the more influential ways of ascertaining whether a financial crisis centered on the stock market is imminent are: (1) the stock price to company earnings ratios (P/E) of stocks, and (2) Warren Buffett’s Expensive Market Rule. The historical average P/E ratio, according to the Shiller Index, is 16. In August 2020, the U.S. stock market was priced at more than twice that, at 35. On Black Tuesday during the 1929 stock market crash, which led to the Great Depression, the P/E ratio had reached 30. The 2000 stock market crash that ended the tech boom of the 1990s occurred when the P/E ratio reached 43.51

According to Buffett’s Expensive Market Rule, the mean average of stock values (measured by Wilshire 5000 market-value capitalization index) as a ratio of GDP is 80 percent. The 2000 tech crash occurred when the stock to income ratio, measured in this way, reached 130 percent, while the 2007 Great Financial Crisis occurred when it reached 110 percent. In August 2020, the ratio was at 180 percent.52

Another key indicator of growing financial instability is the ratio of nonfinancial corporate debt to GDP, depicted in Chart 4. Corporations flush with free cash have taken on debt, available at very low interest rates, in order to further pursue nonproductive ventures such as mergers, acquisitions, and various forms of speculation, using the free cash as flow collateral. In each of the three previous economic crises of 1991, 2000, and 2008, nonfinancial corporate debt reached cyclical peaks in the range of 43 to 45 percent of national income. In 2020, nonfinancial corporate debt in relation to national income reached a record 56 percent. This is a sure sign of a financial bubble stretched beyond its limits.

Chart 4: Debt as a Percent of GDP, U.S. Nonfinancial Corporations, 1949-2020

100vw, 800px” data-lazy-src=”https://monthlyreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2021-01_ROM_chart4-800×529.png” /></a></p>

<p class=) Note: See Chart 3. Based on quarterly data.

Note: See Chart 3. Based on quarterly data.

Source: Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, November 16, 2020, https://fred.stlouisfed.org. Series IDs: BCNSDODNS (Nonfinancial Corporate Business; Debt Securities and Loans; Liability, Level) and GDP.

The entire world economy, apart from China, is now in crisis, with over a million and a half lives lost worldwide to COVID-19 as of the beginning of December, disrupting normal production relations. The International Monetary Fund has projected a -5.8 percent rate of growth in the advanced economies in 2020 and a -4.4 percent rate of growth in the world.53 In these circumstances, there will be no fast recovery from the current capitalist crisis. Heavy storm winds will continue. The U.S. ability to print dollars to stave off financial crises as well as its capacity to devalue its currency so as to increase its exports (thereby reducing the value of dollar reserves held by countries around the world) may both come up against mounting resistance to the dollar system, further hastening the decline of U.S. hegemony. As in other areas, the contagion of capital, which spreads like a virus, ultimately undermining its own basis, is operative here.54 Washington’s attempt to create trade pacts that will ensure the continued dominance of U.S.-centered global commodity chains is running into increasing competition from Beijing. The 2020 Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the largest trade bloc in the world, accounting for around 30 percent of the global economy, has China as its center of gravity.

Faced with economic stagnation, periodic financial crises, and declining economic hegemony, and confronted with rapid Chinese growth, the United States is heading toward a New Cold War with China. This was made clear in the November 2020 U.S. State Department report, The Elements of the China Challenge, accusing the “People’s Republic of China of authoritarian goals and hegemonic ambitions.” The State Department report proceeded to outline a strategy for the defeat of China by targeting the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), exploiting the CCP’s economic and other “vulnerabilities.”55

Here, the chief economic weapon of the United States is its dominance over world finance. Former Chinese Finance Minister, Lou Jiwei, recently indicated that the United States is preparing to launch a “financial war” against China. U.S. attempts at “the suppression of China” by financial means under a Joe Biden administration, he says, “will be inevitable.” Under these circumstances, Lou insists, China’s earlier goals of internationalizing its currency and initiating full capital account convertibility, which would lead to the loss of its control of state finance, are “no longer safe options.” If Washington were to use its power over the world financial system to smother Chinese growth, Beijing, according to Chen Yuan, a former Chinese central bank deputy governor, could be forced to weaponize its holdings of U.S. sovereign debt (totaling $1.2 trillion) in response. This is viewed as the financial equivalent of nuclear war. A financial (not to mention military) war between the United States and China, driven by U.S. attempts to shore up its declining economic hegemony by attempting to derail its emerging rival, could well spell utter disaster for the global capitalist economy and humanity as a whole.56

The Boundary Line and the Contagion of Capital

The crisis of the U.S. system and of late capitalism as a whole is one of overaccumulation. Economic surplus is generated beyond what can profitably be absorbed in a mature, monopolistic system. This dynamic is associated with high levels of idle capacity, the atrophy of net investment, continuing slow growth (secular stagnation), enhanced military spending, and financial hyperexpansion. The inability of private investment (and capitalist consumption) to absorb all of the surplus actually and potentially available, coupled with government deficit spending, leads to growing amounts of free cash in the hands of corporations. The result is the rise of a system of asset speculation that partially stimulates the economy due to the wealth effect (increases in capitalist consumption fed by a part of the increased returns on wealth), but which is unable to overcome the underlying tendency toward stagnation.57

Hence, monopoly-finance capital of today is a deeply irrational system, in which money is seen as begetting more money without the mediation of production, or what Marx characterized as M-M’ (Money-Money + Δm or surplus value).58 “The viability of today’s money manager capitalism,” as the heterodox economist Hyman Minsky called it,

depends upon not having a serious depression: the continued absence of a serious depression fosters experimentation with portfolio managing techniques that increases the likelihood of system threatening crises, that is, increases the likelihood of depressions. There is a basic contradiction in money manager capitalism which makes continued success ever more dependent upon an apt structure of supportive government interventions. Money manager capitalism rests upon the power of government to prevent a sharp decline in aggregate business profits.… We can expect future crises to be met with some form of ad hoc intervention which will in part reflect an unwillingness by policy makers to appreciate that once again capitalism has changed.59

A rational strategy with which to escape this trap—if only partially—would be to increase the direct U.S. governmental role in investment and consumption in order to address the multiple crises of society, including public spending in response to: (1) the climate emergency; (2) the public health crisis; (3) the shortage of adequate housing for much of the population; (4) the deterioration of the public education system under neoliberalism; (5) the absence of a national mass transit system, and so on. Yet, for the government to enter directly into such areas would involve crossing the private sector-government boundary line, which ensures the present near-complete dominance of the economy by the private sector, a phenomenon first critically diagnosed by Marxist economists Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy in Monopoly Capital in 1966.60 As Medlen writes, “the institutional arrangements for profit-seeking investment are simply taken for granted as a boundary line that is not to be violated.”61

So strict is the boundary line in the U.S. economy that outside of the Tennessee Valley Authority, as well as various municipal utilities and land leases, government-owned productive facilities cannot be said to produce internal revenues sufficient to compensate for costs of production. “This is primarily because the government, outside a considerable land mass, the public school system, the U.S. Postal Service and toll-free roads, owns essentially nothing.”62The bulk of federal government discretionary spending goes to the military, which constitutes a huge subsidy to private capital while avoiding any intrusions on the private sector. Meanwhile, the privatization of public health infrastructure and public education is further pushing the boundary line in the direction of the complete dominance of a private sector already prone to overaccumulation and the contagion of capital.

A little more than forty years ago in “Whither U.S. Capitalism?,” Sweezy, writing in Monthly Review, questioned the then common view that the United States, caught in economic stagnation, was headed inevitably to “an American version of the corporate state, authoritarian and repressive internally, increasingly militaristic and aggressive externally.”63 His reasoning is worth recalling today:

There are at least two problems with this “solution” to the crisis of U.S. capitalism. First, it assumes that because the working class has never yet organized itself for effective independent political action it never will in the future either. In my view this reflects a simplistic view of the history of class struggles in the United States and quite unjustifiably rules out the emergence of new patterns of behavior and forms of struggle. Second, it assumes that the capitalists will be united behind a fascist-type policy of repression, and this seems to me doubtful too. Not only is a strategy of this kind costly to large elements of the middle and upper classes, as the whole history of fascism shows, but even more important, it is no solution at all to the real problems of U.S. capitalism. The basic disease of monopoly capitalism is an increasingly powerful tendency to overaccumulate. At anything approaching full employment, the surplus accruing to the propertied classes is far more than they can profitably invest. An attempt to remedy this by further curtailing the standard of living of the lower-income groups can only make things worse. What is needed, in fact, is the exact opposite, a substantial and increasing standard of living of the lower-income groups, not necessarily in the form of more individual consumption: more important at this stage of capitalist development is a greater improvement in collective consumption and the quality of life.64

Sweezy followed this up with the notion of building a “cross-class alliance” between those suffering most from monopoly capitalism and the more far-seeing elements of the ruling class, a kind of new New Deal, but with the working class as the organizing and hegemonic force. This was consistent with a political praxis emphasizing protecting the population in the immediate present while working toward the long-run revolutionary reconstitution of society at large.

More than four decades later, in 2021, the basic conditions are similar, if more serious and threatening. The current struggle for a People’s Green New Deal, based on a just transition, is a call for a cross-class movement to protect humanity as a whole, one which, however, can only be successful by going against the logic of capital and establishing the basis for a new society geared to substantive equality and environmental sustainability: the historical struggle for socialism. If the danger of “a fascist-type policy of repression” of the kind that Sweezy pointed to has reemerged in the twenty-first century in the context of the contagion of capital, so has a new socialist movement from below aimed at ensuring a world of sustainable human development. Predictions as to the future are meaningless in this context. The point is to struggle.

Notes

- ↩ Robert Heilbroner, The Nature and Logic of Capitalism (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), 143.

- ↩ Harold G. Vatter and John F. Walker, The Inevitability of Government Growth (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 6–22; John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney, The Endless Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012), 18–19.

- ↩ Excess capacity is both a cause of the atrophy of net investment, given monopolistic pricing and output strategies, and a manifestation of overaccumulation and stagnation. The issue of excess capacity was extensively examined in Josef Steindl, Maturity and Stagnation in American Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976), 127–37.

- ↩ “Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization in Manufacturing-G17,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November 17, 2020; Foster and McChesney, The Endless Crisis, 20.

- ↩ Timothy Taylor, “Declining U.S. Investment, Gross and Net,” Conversable Economist (blog), February 17, 2017. Productive capacity can of course expand even with no net investment since used up plant and equipment is replaced with more efficient plant and equipment paid out of depreciation funds. Luke A. Stewart and Robert D. Atkinson, “The Greater Stagnation: The Decline in Capital Investment Is the Real Threat to the U.S. Economy,” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, October 2013.

- ↩ Although recognizing that economic surplus can be conceived of as the gross property income from production, in his study, Zhun uses the income of the top 10 percent of the population as a rough proxy for economic surplus, allowing for comparisons between a wide number of countries. He does a reliability check and shows that there is no significant distortion between this method and the two other measures of economic surplus: based on (1) surplus as the residual after essential consumption, and (2) the property share method (used by Thomas Piketty). The top 10 percent method has the advantage of allowing comparisons between a wide variety of countries and historical situations where the data to utilize the other two methods is not available. Zhun Xu, “Economic Surplus, the Baran Ratio, and Capital Accumulation,” Monthly Review 70, no. 10 (March 2019): 25–39; Foster and McChesney, The Endless Crisis, 4; “S. GDP Growth Rate 1961–2020,” Macrotrends. For another article employing the Baran ratio, see Thomas E. Lambert, “Paul Baran’s Economic Surplus Concept, the Baran Ratio, and the Decline of Feudalism,” Monthly Review 72, no. 7 (December 2020): 34–49.

- ↩ In macroeconomic terms, economic surplus that is not invested or consumed (either by private or public entities) represents a loss to society. But the losses do not necessarily fall on corporations and the wealthy—instead, they manifest in the form of “forced dissavings” of the population. Corporations are thus able to use the money capital available to them in other (nonproductive) ways, which have the effect of slowing the rate of growth while also in many cases increasing corporate assets and the earnings on these assets. Economic stagnation under monopoly capital thus leads to a redistribution of wealth and income toward the top.

- ↩ As Michał Kalecki wrote: “A budget deficit has an effect similar to that of an export surplus. It also permits profits to increase above that level determined by private investment and capitalists’ consumption.” Michał Kalecki, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 85; Craig Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality (London: Routledge, 2010), 13. The term free cash was first introduced in Michael Jensen, “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers,” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 76, no. 2 (1986): 322–29.

- ↩ Craig Medlen, “Free Cash, Corporate Taxes, and the Federal Deficit,” Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics 38, no. 1 (2015): 21.

- ↩ Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 6.

- ↩ Medlen, “Free Cash, Corporate Taxes, and the Federal Deficit,” 21, 26. As Medlen writes in connection to the wide definition of free cash, including net interest, “It might be objected that ‘net interest’ ought not to be included in any ‘free cash’ measure as ‘interest’ is a committed obligation. For the portion of the corporate sector whose cash is inadequate to sponsor investment, such ‘interest’ does, indeed, reflect the debt necessary to carry out the given investment expenditure. But since the corporate sector—taken as a consolidated whole—had enough profit and depreciation charges after taxes to fund internal investment, the net interest portion represents free cash on a consolidated basis.” Craig Medlen, “Two Sets of Twins? An Exploration of Domestic Saving-Investment Imbalances,” Journal of Economic Issues39, no. 3 (September 2005): 564.

- ↩ Besides speculation, free cash can also be used for foreign direct investment. On the role of corporate cash flow in the economy, see Thomas B. King, “Corporate Cash Flow and Its Uses,” Federal Reserve Board of Chicago, Chicago Fed Letter 368 (2016).

- ↩ Kalecki, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, 85–86. “Kalecki’s conviction that aggregate demand drove economic activity underpinned his interpretation of accounting identities as ‘models.’ Under the assumption that only capitalists save, an absence of government deficits and export surpluses would mean that ‘capitalists earn what they spend.’ But by providing additional aggregate demand, government deficits act as an artificial ‘export surplus’ that generates additional profits above capitalist’s spending.… Noncorporate deficit spending by consumers and noncorporate businesses has an analogous effect to that of government deficits and adds to the generation of corporate gross profits in excess of corporate investment (free cash).” Medlen, “Free Cash, Corporate Taxes, and the Federal Deficit,” 20, 23. When noncorporate savings minus investment is negative, as it was prior to the bursting of the housing bubble in 2007–08, it contributes to free cash.

In calculating noncorporate S-I , in this formulation, Medlen makes adjustments to avoid double counting. Thus, he subtracts from the free cash the savings from dividends (and savings from net interest in the wide version of free cash), and adds to investment the amount spent on capitalist consumption out of dividends. Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 88.

- ↩ The increased reliance on federal government deficits was connected to reductions in taxes on corporations and the wealthy. See Craig Medlen, “Corporate Taxes and the Federal Deficit,” Monthly Review 36, no. 6 (November 1984): 10–26. The process Medlen identified in the early 1980s was, as is now clear, only in its earliest stages.

- ↩ Joseph A. Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development (New York: Oxford University Press. 1961), 107, 126; Joseph A. Schumpeter, Essays (Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1951), 170; Joan Robinson, Introduction to the Theory of Employment (London: Macmillan, 1937), 11.

- ↩ Kristine W. Hankins and Mitchell Petersen, “Why Are Companies Sitting on So Much Cash?,” Harvard Business Review, January 17, 2020.

- ↩ Chart 2 is derived from Michael W. Faulkender, Kristine W. Hankins, and Mitchell A. Petersen, “Understanding the Rise in Corporate Cash,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 23799, August 2018., Figure 1, 49.

- ↩ If the rate paid on credits secured in part by dependable internal cash flow is lower than that on financial instruments purchased with that credit, “cash management” requires that the latter be pursued.

- ↩ Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 51. Stock values represent discounted profit expectations due to the time value of money. The discount is normally calculated by how many current dollars at the compounded current long-term rate of interest will produce the expected profit at some specific future time. The higher the rate of interest, the larger the discount. And as the interest rates approach zero, the discount—also irrationally—approaches zero. “Minsky moments” when the Fed steps in to reinforce capital to suppress the crisis now occur in every recession, at precisely the moment that the prospects for new investment are at their worst. This has therefore become a regular part of the financialization process with major structural effects. With the lavish provision of central bank credit in spring 2020 at a near-zero rate of interest, the rate of discount went into an asymptotic movement that raised stock values ceteris paribus, but that wildly privileged certain high-growth (monopoly) sectors (communications tech and pharmaceutical) and their stock values. Thus, the value of stocks now became a combination of expected streams of profit from production and evermore extreme discount rates tied to the provision and distribution of central bank credit, that is, stock values now reflect a structure of finance that is relatively autonomous from the real economy.

- ↩ Costas Lapavitsas, Profiting Without Production: How Finance Exploits Us All (London: Verso, 2013); James Tobin, Asset Accumulation and Economic Activity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

- ↩ Chart 3 is derived from Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, Figure 8.3 , 141.

- ↩ The flat line of capital stock to income is a product of the mutual conditioning of investment and national income.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (London: Penguin, 1981), 607–10, 707; Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Selected Correspondence (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 396–402; Jan Toporowski, Theories of Financial Disturbance (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2005), 54; Samir Amin, Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx’s Law of Value (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018), 197. For a detailed description of Marx’s theory of “fictitious capital,” see Michael Perelman, Marx’s Crises Theory (New York: Praeger, 1987), 170–217. See also Foster and McChesney, The Endless Crisis, 55–57.

- ↩ On Piketty’s conflation of capital as the accumulation of fixed stock and “capital” as wealth, see Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 47; Robert M. Solow, “The Rich-Get-Richer Dynamic,” New Republic, May 12, 2014, 51–52; Craig Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 139–40: John Bellamy Foster and Michael D. Yates, “Thomas Piketty and the Crisis of Neoclassical Economics,” Monthly Review 66, no. 6 (November 2014): 11–12.

- ↩ Robin Wigglesworth, “How America’s 1% Came to Dominate Stock Ownership,” Financial Times, February 10, 2020. The logic of this process of wealth concentration under monopoly-finance capital is vicious. As Medlen writes: “In lowering rates of equity returns and interest rates, higher stock valuations drive an ongoing feedback loop that tilts the capital/income ratio upwards. The rate of equity returns and the capital/income ratio are therefore codependent with the interest (discount) rate having a supporting role. Moreover, there is an amplification effect: An expectation of lower and lower rates of return on equity and bonds is compensated by a larger offsetting gain in capital values thereby driving a higher and higher share of income towards the wealthy.” Craig Medlen, “Piketty’s Paradox, Capital Spillage, and Inequality,” Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics 40, no. 4 (2017): 630.

- ↩ “If you multiply the rate of return on capital [wealth] by the capital-income ratio, you get the share of capital in the national income.… It is always the case that wealth is more highly concentrated among the rich than income from labor…and this being so, the larger the share of income from wealth, the more unequal the distribution of income among persons is likely to be.” Solow, “The Rich-Get-Richer Dynamic,” 53.

- ↩ Robert M. Solow, “The Rich-Get-Richer Dynamic,” 52.

- ↩ This is often called the capital output ratio, though it is more properly referred to as the wealth/income (output) ratio.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney, “Surveillance Capitalism,” Monthly Review66, no. 3 (July–August 2014): 1–31; Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: Public Affairs, 2019).

- ↩ Ronald Surz, “If COVID-19 Won’t Pop the Stock Market, What Will?,” Nasdaq, August 20, 2020. Jacob A. Robbins, “Capital Gains and the Distribution of Income in the United States,” National Bureau of Economic Research (2018). It is the nature of asymptotes to signal a contradiction in the system under study that presages a qualitative change—here, the divergence between hypertrophied finance, asset prices, and the value of labor.

- ↩ Kalecki, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, 85.

- ↩ Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 112–13; Intan Suwandi, R. Jamil Jonna, and John Bellamy Foster, “Global Commodity Chains and the New Imperialism,” Monthly Review 70, no. 10 (March 2019): 1–24.

- ↩ For the basic data on affiliates abroad and exports, see Bureau of Economic Analysis, “International Data, Direct Investment and MNE, Data on Activities of Multinational Enterprises, U.S. Direct Investment Abroad, All Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates (Data for 2009 and Forward), Goods Supplied,” and “International Data, Direct Investment and MNE, Data on Activities of Multinational Enterprises, U.S. Direct Investment Abroad, All Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates (Data for 2009 and Forward), S. Exports of Goods,” accessed December 8, 2020; Craig Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 121.

- ↩ “National Data, National Income and Product Accounts, Tables 6.16A, 6.16B, 6.16C, 6.16D Corporate Profits by Industry,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed December 11, 2020, lines 2 (Domestic Industries) and 5 (Rest of the World); Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 126. See also Joe Weisenthal, “Chart of the Day: What Percent of Corporate Profits Come from Overseas?,” Business Insider, May 17, 2011; “The share of national corporate profits accounted for by foreign profits (receipts from the rest of the world) has trended upwards for the last 60 years, peaking at 45.3 percent in 2008.” Andrew W. Hodge, “Comparing NIPA Profits with S&P 500 Profits,” Survey of Current Business (March 2011): 23.

On “imperialist rent” see Amin, Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx’s Law of Value, 110–11; Foster and McChesney, The Endless Crisis, 140, 173; Kenneth L. Kramer, Greg Linden, and Jason Dedrick, “Capturing Value in Global Networks,” Paul Merage School of Business, University of California, Irvine, July 2011, 5, 11; John Smith, Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2016).

- ↩ Intan Suwandi, Value Chains (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2019); Foster and McChesney, The Endless Crisis, 140, 171–73.

- ↩ Nicholas Shaxson, Treasure Islands (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

- ↩ Martin Feldstein, “Resolving the Global Imbalance: The Dollar and the U.S. Saving Rate,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 3 (2008): 115.

- ↩ Rob Wallace, Dead Epidemiologists: On the Origins of COVID-19 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020), 42–57; John Bellamy Foster and Intan Suwandi, “COVID-19 and Catastrophe Capitalism,” Monthly Review 72, no. 2 (June 2020): 1–20.

- ↩ Robert G. Wallace et al., “The Dawn of Structural One Health: A New Science Tracking Disease Emergence Along Circuits of Capital,” Social Science and Medicine 129 (2015): 68–77.

- ↩ Lorie K. Logan, “Treasury Market Liquidity and Early Lessons from the Pandemic Shock” (speech, Brookings-Chicago Booth Task Force on Financial Stability Meeting, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, October 23, 2020).

- ↩ Fred Imbert and Pippa Stevens, “S&P Index Jumps More than 1%, Capping Off Its Best Week Since 1974,” CNBC, April 9, 2020.

- ↩ Mark DeCambre, “Wall Street Profits Soared in First Half of 2020 Amid the Worst Pandemic in a Century, Report Says,” Market Watch, October 20, 2020.

- ↩ “Billionaires Pandemic Wealth Gains Burst through $700B,” Americans for Tax Fairness, July 16, 2020.

- ↩ “Billionaires’ Net Worth Grows to $10.2 Trillion During Pandemic,” teleSUR, October 7, 2020. Congressional Research Service, “USDA Domestic Food Assistance Programs: FY2019 Appropriations,” May 24, 2019, 3, Table I.

- ↩ “If you multiply the rate of return on capital [wealth] by the capital-income ratio, you get the share of capital [as a flow] in the national income. For example, if the rate of return is 5 percent a year and the stock of capital is six years’ worth of national income, income from capital will be 30 percent of national income, and so income from work will be the remaining 70 percent.… As long as the rate of return exceeds the rate of growth, the income and wealth of the rich will grow faster than the typical income from work. (There seems to be no offsetting tendency for the aggregate share of capital to shrink.)” Solow, “The Rich-Get-Richer Dynamic,” 53.

- ↩ Heidi Shierholz, “More than 25 Million Workers Are Being Hurt by the Coronavirus Downturn,” Economic Policy Institute, November 6, 2020.

- ↩ Bridget Balch, “54 Million People in America Face Food Insecurity During the Pandemic. It Could Have Dire Consequences for Their Health,” Association of American Medical Colleges, October 15, 2020.

- ↩ Financial Health Network, S. Financial Health Pulse: 2020 Trends Report (Chicago: Financial Health Network, 2020).

- ↩ “The Conference Board Economic Forecast for the U.S. Economy,” Conference Board, November 13, 2020.

- ↩ Robert Francis, “FAANG Stocks and COVID-19,” Global Banking and Finance Review, October 11, 2020.

- ↩ Surz, “If COVID-19 Won’t Pop the Stock Market, What Will?”

- ↩ Surz, “If COVID-19 Won’t Pop the Stock Market, What Will?”

- ↩ “Real GDP Growth, Annual Percent Change, 2020,” International Monetary Fund, accessed November 21, 2020.

- ↩ See Samir Amin, The Liberal Virus (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2004).

- ↩ Policy Planning Staff, Office of the Secretary of State, Elements of the China Challenge(Washington DC: Office of the Secretary of State, 2020).

- ↩ “Former China Finmin Says Trade Frictions with U.S. Could Remain Under Biden,” Nasdaq, November 11, 2020; “China-U.S. Rivalry on Brink of Becoming a ‘Financial War,’ Former Minister Says,” South China Morning Post, November 9, 2019; Julian Gewirtz, “Look Out: Some Chinese Thinkers Are Girding for a ‘Financial War,’” Politico, December 17, 2019.

- ↩ On the wealth effect, see Dean Baker, The End of Loser Liberalism(Washington DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2009), 18; Christopher D. Carroll and Xia Zhou, “Measuring Wealth Effects Using U.S. State Data,” Federal Reserve Board of San Francisco, October 26, 2010.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, vol. 3, 515.

- ↩ Hyman Minsky, “Financial Crises and the Evolution of Capitalism,” in Capitalist Development and Crisis Theory, ed. Mark Gottdiener and Nicos Komninos (London: Macmillan, 1989), 398, 402. See also Riccardo Bellofiore, “Hyman Minsky at 100: Was Minsky a Communist?” Monthly Review 71, no 10 (March 2020): 6–10.

- ↩ Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966), 161–75.

- ↩ Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 5.

- ↩ Medlen, Free Cash, Capital Accumulation and Inequality, 149.

- ↩ Paul M. Sweezy, “Whither U.S. Capitalism?” Monthly Review 31, no. 7 (December 1979): 11.

- ↩ Sweezy, “Whither U.S. Capitalism?” 12.